An unusual, and probably new, form of hepatitis has appeared in a number of countries this year, first being noticed in the UK, then spreading to Spain and the Netherlands and on to at least 35 other states and territories including the USA. The first group of active cases were found in March with the latest case numbers estimated at over 1000 and 22 deaths. Unusually, and alarmingly, all of the known cases have been in children. A number have required transfer to specialist children’s liver units, with a number needing lifesaving liver transplants.

The most common symptoms of the mysterious hepatitis are vomiting and jaundice: jaundice is a well-known symptom of serious hepatitis, as damaged livers can lead to high levels of bilirubin (a yellowy-orange bile pigment) in the body, which turns the skin and the whites of the eyes a yellow colour. At the time of writing, the Royal Australian College of General Practice (RACGP) had reported that at least five of the infected children have died.

Not A, B C, D or E

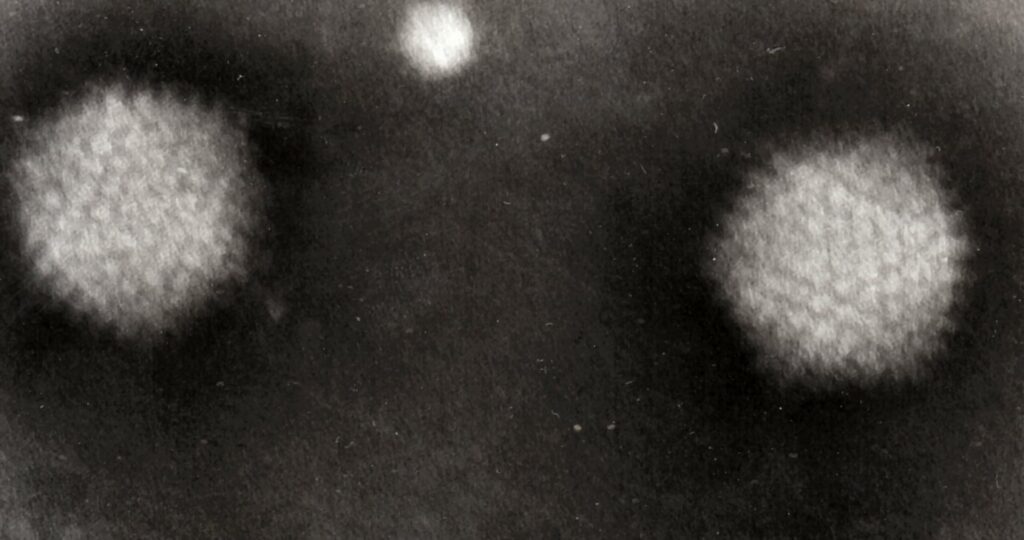

Lab tests on all of those infected have excluded hepatitis viruses A, B, C, D (where applicable, as D only exists in some people living with hepatitis B) and E. Notably, a number of patients (at least 15%) have had severe COVID-19 infections, but given the overall high rate of infection in the UK generally, it is possible that this could well be coincidence instead of cause. Both COVID-19 and the unknown hepatitis being new viruses developing at around the same time may mean they are linked, or it may be a confusing case of bad luck.

Importantly, there is no sign of any link to COVID-19 vaccination: indeed, the majority of affected children are under five years old, and so too young to have received any COVID-19 vaccine.

One study found that an adenovirus—a type of common virus that typically causes mild cold- or flu-like illness—was present in around two-thirds of the infect UK children. In this case it was usually adenovirus 41, which more commonly causes diarrhea in children. A number of the cases which did not show the adenovirus being present were not properly tested, so its presence cannot be ruled out.

However, since it is very unusual to see hepatitis develop following an adenovirus infection in previously well children, clinical investigations are continuing into other factors which may be contributing, though no other epidemiological risk factors have been identified to date, including recent international travel. Some media outlets claimed research found that cases were linked with exposure to dogs, but the evidence for this is very weak and not well supported.

Though the first cases were found in March, retrospective testing of children who had shown similar health problems has found cases going back to October 2021. Laboratory testing for additional infections, chemicals and toxins is underway for the identified cases.

Dr Renu Bindra, Senior Medical Advisor at the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), said, “It’s important that parents know the likelihood of their child developing hepatitis is extremely low. However, we continue to remind everyone to be alert to the signs of hepatitis—particularly jaundice, look for a yellow tinge in the whites of the eyes—and contact your doctor if you are concerned.

“Our investigations continue to suggest that there is an association with adenovirus infection, but investigations continue to unpick the exact reason for the rise in cases.”

The UKHSA, the US Centers for Disease Control and other national health agencies continue to monitor the spread of the infection as they try to learn more about its cause and health effects.

In Australia

In April, Gastroenterological Society of Australia (GESA) paediatric hepatologist Professor, Winita Hardikar, said that although each year in Australia, a small number of children present with unexplained hepatitis, with some requiring a liver transplant, there had not been an unusual spike.

In its media statement, GESA said cases of mystery hepatitis in Australian children “is a rare occurence”, and ongoing surveillance in Australia is occurring.

“Practise thorough handwashing, including supervising children,” the GESA statement advised. “Cover mouth and nose when coughing or sneezing.”

It advised parents to be alert to symptoms — which may include nausea, vomiting, abdonimal pain, loss of appetite, fever. jaundice, dark urine and pale faeces — and to contact their doctor if they have any concerns.

For more information, contact GESA on gesa@gesa.org.au