In 2022 an unusual, and probably new, form of hepatitis began to appear in a number of countries, being first noticed in the UK, then spreading to Spain and the Netherlands and on to at least 35 other states and territories including the USA. Unusually, and alarmingly, all of the known cases were in children. A number required transfer to specialist children’s liver units, with some needing lifesaving liver transplants.

The most common symptoms of the mysterious hepatitis were vomiting and jaundice: jaundice is a well-known symptom of serious hepatitis, as damaged livers can lead to high levels of bilirubin (a yellowy-orange bile pigment) in the body, which turns the skin and the whites of the eyes a yellow colour. We first reported on this outbreak in the Hepatitis SA Community News in 2022.

Now, a world-first analysis of the outbreak by researchers at the University of Sydney has found that the primary suspect is highly likely to be an infection by multiple viruses. However, many questions still puzzle the researchers. The outbreak affected only children under the age of 10, and, within a year, more than 1,000 children from 35 countries with hepatitis of unknown origin were reported to the World Health Organization. But after 12 months, cases seemed to stop just as quickly as they appeared.

…there was no clear link that could explain how the outbreak crossed continents.

The study found evidence that supports an existing theory that the mysterious hepatitis was caused by an infection of different viruses at the same time, but also reveals cases were higher and more severe than initially thought. In the end, six percent of the reported cases needed liver transplants.

However, inconsistent surveillance and monitoring by health agencies means that questions around the outbreak are only half-answered, including why cases were reported only in certain countries.

“When the outbreak unfolded, the increase of cases was baffling. It was intriguing as to how these cases occurred and why there were cases from the United Kingdom as well as cases from the United States,” said study co-author Professor Guy Eslick from the Australian Paediatric Surveillance Unit at the University of Sydney. The first reported cases were in the UK, and then the US, particularly in the state of Alabama. However, there was no clear link that could explain how the outbreak crossed continents.

“It was a medical mystery we wanted to investigate. In this study, by bringing together all available evidence, we can form a clearer picture about the cause of the outbreak. This will be crucial for the identification and prevention of future outbreaks,” Professor Eslick explained.

The research team pooled evidence from all available studies reporting on cases of hepatitis of unknown origin, where doctors were unable to determine the cause. The team found that the number of cases were higher and more severe than initially thought, with the data revealing more than 3,000 cases. The mortality rate was 3.5%. As we reported at the time, there was also strong evidence supporting a leading theory the hepatitis was caused by infection of different viruses at the same time.

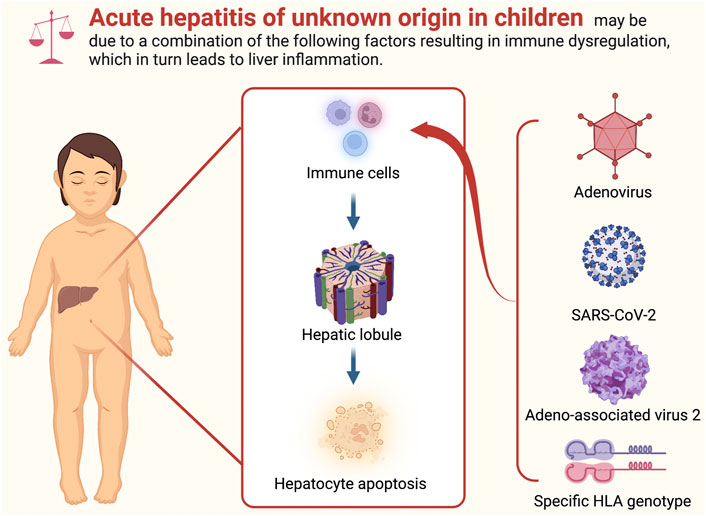

A common childhood virus called adeno-associated virus 2 (AAV2) was present in blood and tissue samples from the majority of children with unexplained hepatitis, and many were infected by multiple ‘helper viruses’. AAV2 cannot multiply unless there is a ‘helper virus’ to kickstart the infection, which can include other common childhood respiratory and intestinal viruses, such as adenovirus, enterovirus, rhinovirus (common cold) and herpes viruses. In some patient samples, SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) was also detected.

The timing of the outbreak and the COVID-19 pandemic potentially also had a role. After COVID-19 pandemic restrictions were lifted, young children who had been isolated may have had immune systems less trained to fight off common childhood infections. But many questions continue to puzzle researchers. These include how the outbreak appeared, and if there could be a genetic link that made some children more vulnerable in developing severe hepatitis than others. Another question is why certain countries were major epicentres of the outbreak, with cases concentrated in the UK and US. Although there were cases in New Zealand, there were no cases in Australia.

The findings were published in the Journal of Infection, and although they offer a clearer picture of the outbreak, Professor Eslick noted that our understanding of the 2022 hepatitis of unknown origin outbreak is still incomplete. There was inconsistent reporting and surveillance of the outbreak between countries already under pressure managing the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Australian Paediatric Surveillance Unit is continuing to monitor for hepatitis cases of unknown origin. They have been monitoring all cases of severe acute hepatitis in children and adolescents, not just the unknown cases. However, Professor Eslick said further research is required. Since the 2022 outbreak, monitoring by many health agencies overseas, such as the American CDC, for similar hepatitis cases in children has stopped.

“The lesson from all past and present disease outbreaks is the need to be continually vigilant. This is something we need to continue investigating,” Professor Eslick said.

Last updated 10 April 2025

More from:

Enjoyed this article? Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish new stories.

Subscribe for Updates