Three Hepatitis SA delegates to the 2023 Harm Reduction International Conference in Melbourne, share their experience and takeaways from the event.

Carol Holly

The Harm Reduction conference is held in a different country every two years and provides a forum for sharing the latest research, programs and policy in drug use, harm reduction* and human rights. The conference is convened by Harm Reduction International (HRI) – an organisation that promotes harm reduction and rights-based, evidence-based responses to drug use.

What I like about the HRI conference is that HRI always works in partnership with the local Drug User Organisation or peer program to facilitate drug users’ participation in the conference. As the conference was held in Melbourne this year, the local peer-based organisation Harm Reduction Victoria co-hosted the conference.

Awards were given out at the Opening Ceremony, and the inaugural Gill Bradbury Award (awarded to an individual, group or organisation providing excellent services to people who use drugs) went to the AIVL National Peer Network, of which the Hepatitis SA CNP Peer Projects is a member. It was great to see peers’ contribution to harm reduction acknowledged on an international level.

This year the overarching themes were drug law reform (decriminalization of small quantities of drugs for personal use and/or the sale of small quantities of drugs ie ‘user dealers’) and ‘safer supply’, as a result of the tragic impact of fentanyl and its analogues. Fentanyl and fentanyl analogues have contributed to the deaths of many tens of thousands of people in the US and Canada. I can only be thankful that fentanyl has not made huge inroads into the Australian supply but I believe that we must have our SA response prepared if/when it does.

The conference presentations and panel discussions were enlightening but it is the opportunities for networking and sharing experiences that I will remember for longer. I was inspired by hearing about civil disobedience and what’s happening on the ground to improve the lives of people who use drugs.

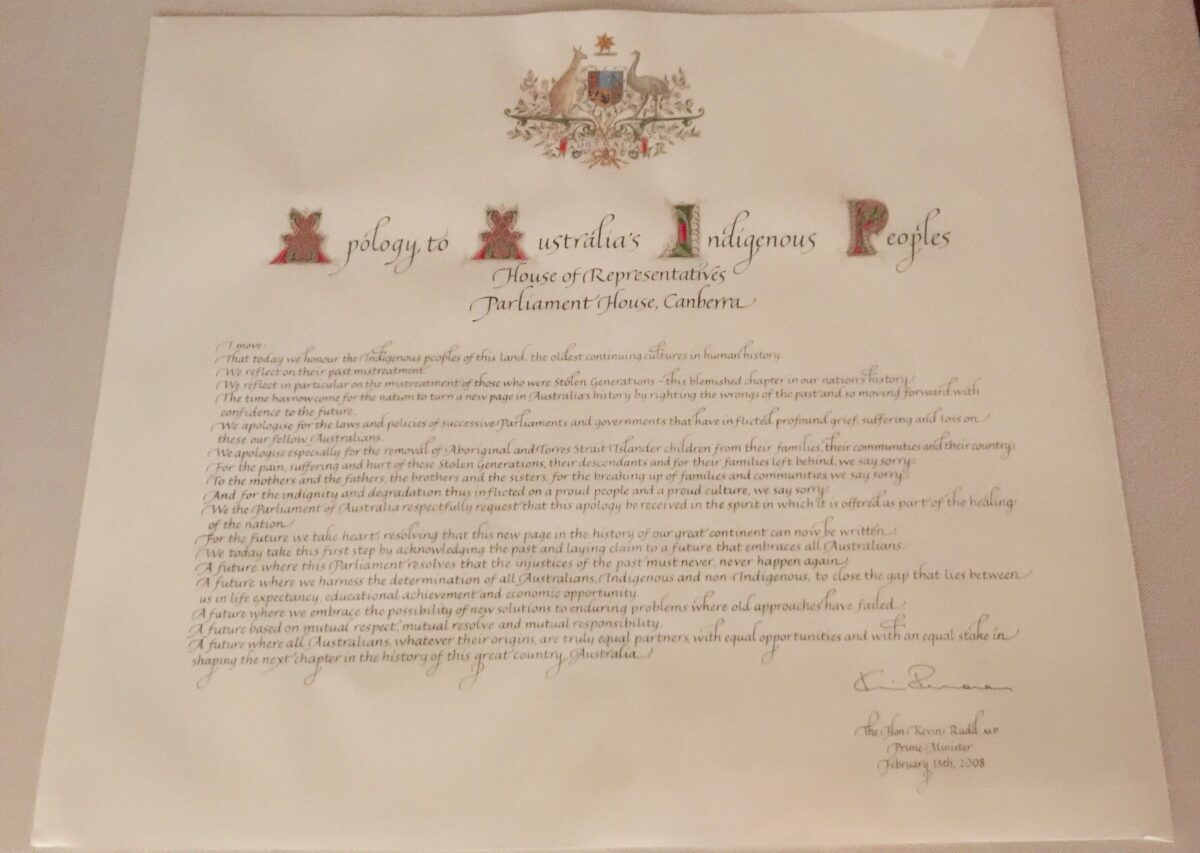

I participated in the workshop to develop the Conference Declaration, which was read out at the closing ceremony. The Melbourne Declaration advocates for the genuine inclusion and representation of people who use drugs, demands equitable health and social outcomes and an end to criminalisation and prohibition of drug use.

*Harm reduction refers to policies, programmes and practices that aim to minimise the negative health, social and legal impacts associated with drug use, drug policies and drug laws. Harm reduction is grounded in justice and human rights. It focuses on positive change and on working with people without judgement, coercion, discrimination, or requiring that people stop using drugs as a precondition of support.

Margaret Randle

This was the first Harm Reduction Conference since 2019 and everyone was excited to hear what Australia had been doing as an early adopter of health-based approaches to drug use. I wanted to hear about what was going on in the Southeast Asian region, as they are our closest neighbours and notoriously hard-line on drug users, with alarming rates of incarceration of women and the use of death penalties for drug offences. Sadly, most of the would-be attendees from Southeast Asia were not given visas.

The conference went for three days: each day we had about 30 presentations to choose from. It was mind-boggling. I would choose something and then question whether I had made the right choice.

Most of the presentations I saw were about peers or civil disobedience, focusing on people who had made the choice to do something that was illegal but ethically right. For instance, in Dublin a small organisation had bought a van, which they would park in an alleyway at a certain time of day. This van was an injecting room. Dublin had people injecting and overdosing in the street, so if they could inject safely in a van with a couple of people around them and naloxone on hand, isn’t that a good thing?

The police would come and ask them to open up, which they would do after the person had injected the drugs. The police could do nothing as the drugs were gone. Of course, police don’t like this kind of thing and pursued the van with a vengeance. One staff member ended up being arrested and charged for not unlocking the van and for obstructing police. He went straight back out the next day.

Often their clients were in wheelchairs and needed to be lifted in and out of the van, which was not an easy feat. This van led to changes for injecting drug users in Dublin. The power of people is enormous.

Thinzar Tun from Myanmar’s presentation was called “If there is a will there is a way!—A peer-led Women’s Cost Effective Service Delivery in Rural Areas of Myanmar”. Drug-using women in Myanmar are discriminated against and looked down upon. They struggle to get through each day with no money, no transport and no support from anybody.

They paid peer workers to ride motor bikes into rural areas to meet female drug users where they wanted to be met: in shooting galleries, in brothels, and on the street. There they helped them with day-to-day things such as medical appointments and picking up their methadone supplies.

This project helped 194 women in the first year. The cost for each peer, with a bike, was only $37 per year—such a small amount of money to increase women’s quality of life. The only question I had for Thinzar Tun was why did they only employ male peers? Perhaps it had something to do with the funding, or maybe they were the only drug users they could hire.

Most of the presentations I saw were from countries that have a huge opioid problem, such as Canada, the US and the UK. As drug users are dying by the thousands, the governments and the communities look the other way when people try to do something to ease the pain of all of these deaths, such as having a shop in Canada to sell quality-tested drugs openly to people. As always, effective harm reduction is the only way forward.

Australia is in a different position, as methamphetamine is the favoured drug here. We don’t have massive amounts of opioid deaths, though some people want you to think we do. Sadly, Australia is lagging hopelessly behind and I honestly think people attending the conference might have been disappointed with what we have been doing in the harm reduction and peer space.

I met so many amazing people at this conference, from Canadian drug users to Norwegian nurses. Each and every one of them has a passion for harm reduction and helping the most stigmatised communities in the world. After three days I was exhausted but happy.

Megan Stanfield

I was lucky enough to attend HR23 this year, it’s the first time I’ve attended anything like that before and found it to be a great opportunity to network with people from other organisations as well as hear about what’s going on in the world of Harm Reduction. I especially liked meeting the workers from Harm Reduction Victoria and loved the display they had set up!!

In one of the sessions the Eliminate C campaign was mentioned and as Penni (a colleague) and I were involved in promoting it in the city centre last year, I was wrapt to hear it had been one of the most successful campaigns thus far.

I also heard several speakers talk about their harm reduction efforts in countries such as Myanmar and couldn’t help but think that they’ve really got their work cut out for them. After that I’ll never complain about having to get up for work again…. Well maybe just a little….

Last updated 22 March 2024

More from:

Enjoyed this article? Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish new stories.

Subscribe for Updates