Hepatitis Australia is currently developing a campaign to reach baby boomers and other community groups who may have been missed in past hepatitis C awareness raising efforts.

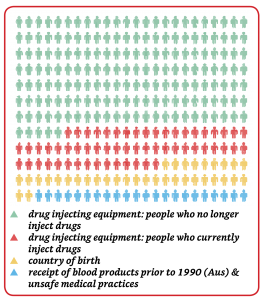

Almost eight out of ten people living with hepatitis C are not current injecting drug users. Although the majority of Australians who acquire hepatitis C did so through unsafe injecting, 67 per cent (124,590) of them are no longer injecting drug users.

Close to 230,000 people were living with hepatitis C at the end of 2015. Of these, 25,000 (11%) were born overseas in regions of high prevalence and almost 16,000 (7%) contracted the virus through transfusion of unscreened blood and blood products, unsterile medical procedures, or mother-to-child transmission.

These numbers, presented in the Reaching Out: Part 1 report from Hepatitis Australia, suggest that a vast majority of those who need to be reached for testing and treatment are not necessarily engaged with the usual services where such information is being disseminated.

The Reaching Out project is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health. Its brief is to “develop and deliver general education and awareness on hepatitis C, available testing and treatment options to individuals with hepatitis C who have either not injected drugs or have done so in the past but no longer identify as a person who injects drugs.”

The project does not suggest that people who inject drugs were any more or less deserving of access to treatment than any other group. Rather, it indicates that if Australia is to eliminate hepatitis C by 2030, there need to be ways of getting the test and treat message out to the diverse group of people who live with hepatitis C.

Part one of the three-stage Reaching Out project looked at estimates and projections of people with hepatitis C in Australia as well as the demographics.

The report identified key non-injecting user communities who may have higher prevalence of hepatitis C. They include:

- people who previously injected drugs;

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities;

- people born overseas in high prevalence and high disease burden countries and regions including Egypt, Pakistan, China, Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe and Latin America;

- people who have received unsafe tattooing and/or body piercing;

- gay and bisexual men who have HIV;

- people with bleeding disorders;

- people with medically acquired hepatitis C;

- children born to women with hepatitis C, and

- other people with hepatitis C who may not be engaged in clinical care such as war veterans and people who use performance and image enhancing drugs.

While the exact number of Australians living with hepatitis C who do not identify as a person who injects drugs is not known, information suggests that the group is extremely diverse. The purpose of the report was to synthesise evidence which can be used to develop tailored communication and engagement strategies for these groups.

Reaching Out Part Two, which looks at strategies for connecting people living with hepatitis C to clinical care, is also available and may be read online here.

The project is currently developing useful, accessible information resources to support the awareness campaign. If you work with any of the communities mentioned above, please feel free to contact us with your suggestions and ideas.

This article first appeared in the Hepatitis SA Community News, issue 75. Read more here.