Despite having been one of the countries leading in the global campaign to eliminate viral hepatitis, Australia may now not meet its 2022 national hepatitis C treatment target or the 2030 global target.

The proportion of people with hepatitis C taking up treatment has dropped steadily since the initial surge in 2016. Although close to half of Australians living with hepatitis C have been treated since, we will not meet our national target of having 65% treated by 2022 if the decline continues. Nor will we meet the 2030 global target of treating 80% of people with hepatitis C.

These were key findings from the Viral Hepatitis Mapping Project National Report 2020.

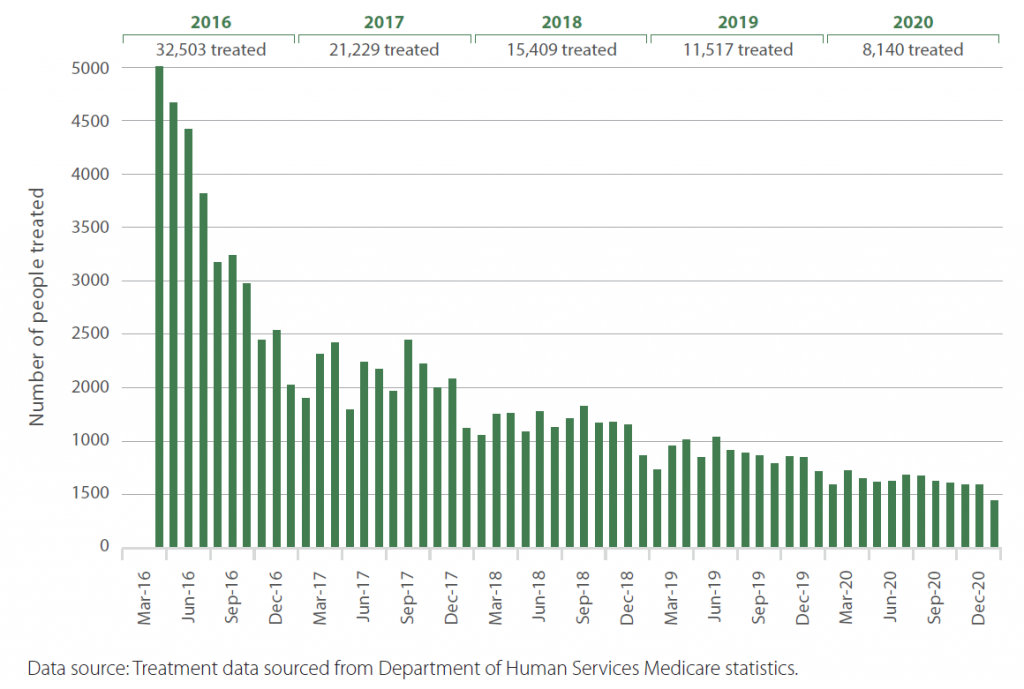

CHC treatment in Australia, by month, March 2016 – December 2020

At the start of 2016, there were close to 189,000 people living with hepatitis C in Australia. Between 2016 and 2020, close to 88,800 people received hepatitis C treatment. This brought the number of people with chronic hepatitis C was just over 122,260 at the end of 2019, including new diagnoses.

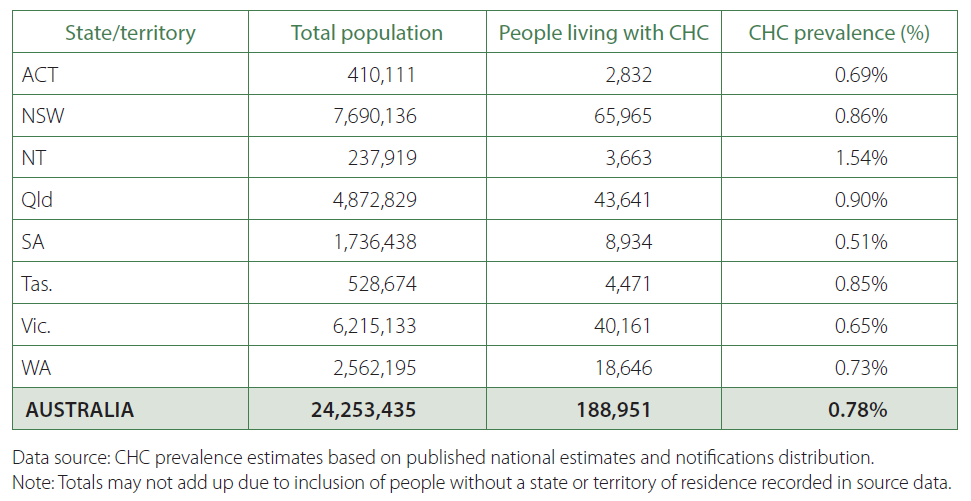

South Australia which has the lowest hepatitis C prevalence (0.51%) at the start of 2016, is also the state with the highest rate of treatment uptake (58%). The highest hepatitis C prevalence (1.54%) among the eight states and territories is in the Northern Territory which has the lowest treatment uptake (21.6%).

Estimated prevalence of CHC, by state and territory, start of 2016

The Report said in order to reach the National Strategy target of 65% uptake by 2022, an additional 34,000 people would need to be treated. This translates to 17,000 treatment uptakes a year – double the number that received treatment in 2020. In other words, treatment numbers need to increase dramatically in order to meet the 2022 target.

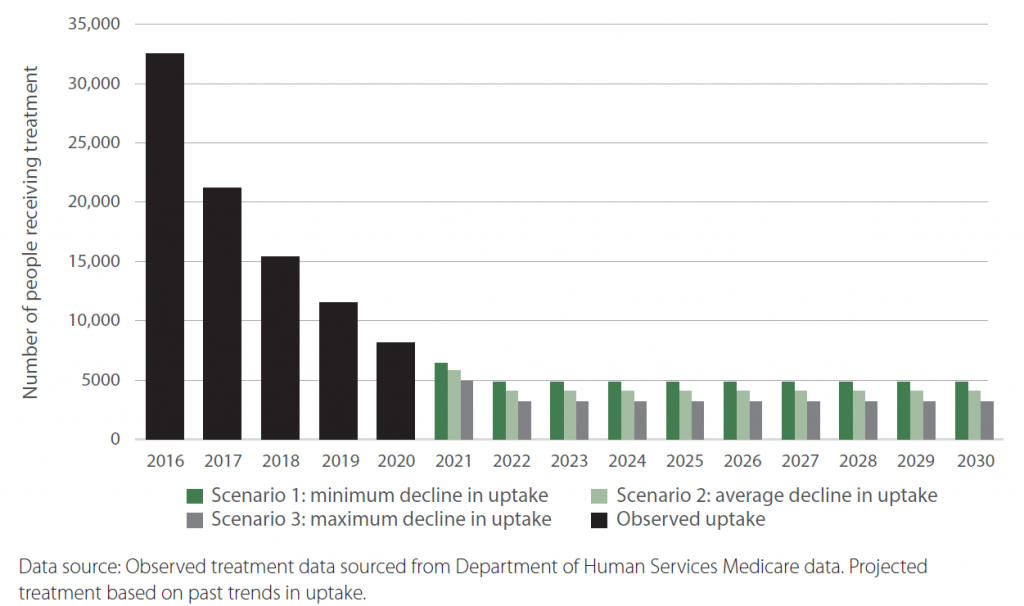

If the current reduction in treatment uptake is not reversed, modelling shows that Australia will not reach the 2022 target of 65% treatment. Neither would any individual state or territory although South Australia would be close (64.5%) under a scenario which assumes a minimum decline in treatment uptake.

The Challenges

Although it would have been convenient to blame the COVID-19 pandemic for the decline in treatment rate, the decline in treatment rate which began almost immediately after the high uptake in 2016 indicates a trend, not a pandemic-induced blip.

There was, however, a bigger drop in treatment rate in 2020, exacerbating the problem, especially in rural and regional areas.

“Despite national trends remaining relatively stable, some PHNs experienced a significantly greater decline in hepatitis C treatment uptake during 2020 than they had during previous years, suggesting an effect on treatment uptake from the COVID-19 pandemic and resultant restrictions. As expected, this was more pronounced in those regions where cases of COVID-19 were most concentrated, such as NSW and Vic,” the Report said.

Hepatitis C Treatment Uptake by Remoteness 2016 to 2020

Numerically there are more people with chronic hepatitis C in urban areas but the rate of infection is in fact higher in rural and regional areas, and the rate of treatment uptake lower. The seven Primary Health Network (PHN) areas with the lowest treatment uptake all had above average prevalence and were predominantly outside metropolitan areas.

Non-metropolitan areas have less access to specialist services and more people who are socially and economically disadvantaged. This mix of factors makes it harder to identify the key reason for lower treatment rates in some PHNs. Reasons most likely vary between regions and communities.

“There is still a sizeable proportion of the high-risk population who are not treated.” – Prof Greg Dore

For instance, screening and testing people in rural and remote Aboriginal communities can be particularly challenging. Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia STIBBV Program Coordinator, Josh Riessen, pointed out that the tasks of identifying and referring at-risk clients are more challenging for rural health workers. Information they need to assess if a client is at risk may not be readily at hand, and there are no friendly GPs or nurses in the neighbourhood to whom they can refer their clients. On top of this, the worker needs to attend to all of the client’s other health issues.

Other hard-to-reach groups include people on the fringe. At the recent Second National Viral Hepatitis Elimination forum, Professor Greg Dore from the Kirby Institute said that not all of the undiagnosed people living with hepatitis C are in the mainstream. “There is still a sizeable proportion of the high-risk population who are not treated,” he said. “These are people at the edges, people who are not currently injecting and so not accessing services, vulnerable people without housing… transient populations.”

Next Steps

Australia’s early success in tackling hepatitis C can start lagging if we don’t find ways to change the current downward trend in treatment uptake.

Observed uptake and projected future CHC treatment trends, based on 3 yearly change trends, 2016–2030

Suggestions from Professor Dore include re-framing how we think about our success or the lack of it. “We should be looking at other things, such as better surveillance of new infections, so we can identify the prevalence of active infection in priority population groups,” he said. “Tracking this could help us break the back of this epidemic.”

Other forum participants at the Viral Hepatitis Elimination forum suggested actively adopting programs or pilots that work so that they become standard practice rather than a novelty, and working at community levels to achieve micro elimination.

Scaling up prescribing by General Practitioners (GPs) and other non-specialist providers is possibly another way to increase access to treatment, especially in rural and regional areas. According to the Report, PHNs with a higher proportion of GP prescribing saw less significant declines in treatment uptake during the pandemic.

None of these actions by themselves would fix the downward trend. What’s needed is a coordinated strategy that pulls effective solutions together into a concerted effort, and adequate funding to implement the strategy.