The hepatitis B virus (HBV) is notoriously hard to get rid of. The virus embeds its covalently closed circular DNA (the cccDNA) in the liver, integrating itself into the host cells. Current therapies work either by ‘managing’ the virus to stop or reduce replication or strengthening the body’s immune system to fight against and suppress the virus. There is as yet no cure and treatment is usually long-term, if not life-long.

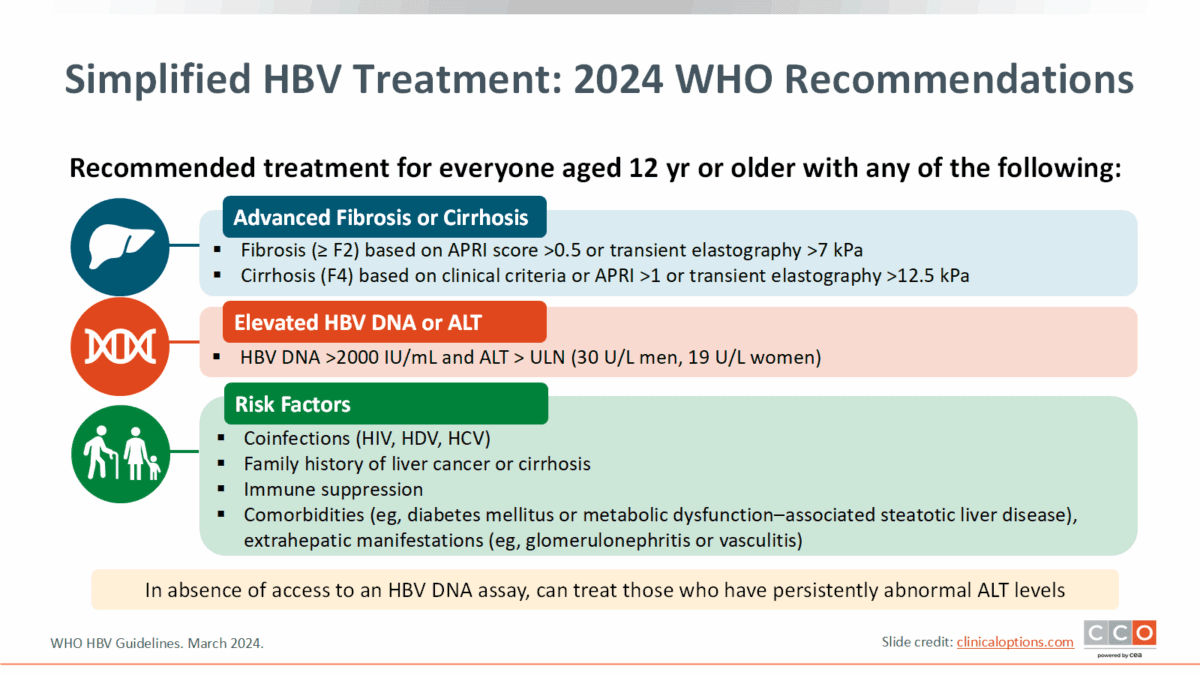

Although researchers are moving towards treatments that would achieve what is known as a functional cure – a state where the hepatitis B virus’s cccDNA is undetectable, and there is a loss of hepatitis B surface antigens – until such therapy is available, there is concern about people developing resistance to the medications over time, reducing drug efficacy and options. This in turn often leads to a reluctance to start treatment unless strict criteria are met.

This has contributed to a situation where the hepatitis B treatment rate is low and adherence often poor, leading to adverse outcomes which could be avoided. There is an emerging awareness among health professionals and related organisations of a need to change the approach to chronic hepatitis B care even as the community awaits the arrival of a functional cure.

Key recommendations for changes in hepatitis B care can be summarised as: universal screening, earlier treatment, and treat more people.

In a discussion paper entitled Bridging the Gap to a Functional Cure for Hepatitis B, prominent hepatitis B health care professional and advocate Dr Su Wang said that while work progresses towards a functional cure, there are many things that need to be done now to get more people diagnosed and into care.

Dr Wang pointed out that only 13% of people living with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) have been diagnosed, and only 3% have received treatment, and, as a result, liver cancer rates are still on the rise.

“The CDC (Center for Disease Control) now recommends universal HBV screening and vaccination. Now is the time to scale up screening so more know their HBV status. Most of the liver societies are also updating HBV treatment guidelines this year and we anticipate the expansion of treatment eligibility.

Some experts believe that HCPs should approach HBV as ‘prove to me you don’t need to be treated’.

“We are seeing an evolution in our approach in HBV treatment with an openness to starting antivirals earlier. Antivirals are safe, effective at suppressing the virus, and have become more affordable with the availability of generic medications,” she said.

On concerns around drug resistance, Dr Wang said the risk/benefit balance of initiating treatment has shifted. “In the past, there was concern about the high risk of developing resistance with lamivudine, but that is less of a concern with tenofovir and entecavir,” she said.

“Although our current treatments are not a cure, controlling viral replication is important for preventing the inflammation that drives development of cirrhosis and cancer, subsequently improving patient outcomes.

“Our previous strict approach of obtaining frequent labs to ‘prove people needed to be treated’ led to many individuals not receiving treatment and falling out of care. Many people living with CHB were told by their HCPs (health care providers) that they didn’t need medication, and some resorted to taking ineffective and potentially harmful herbal medications and supplements. Some experts believe that HCPs should approach HBV as ‘prove to me you don’t need to be treated’.”

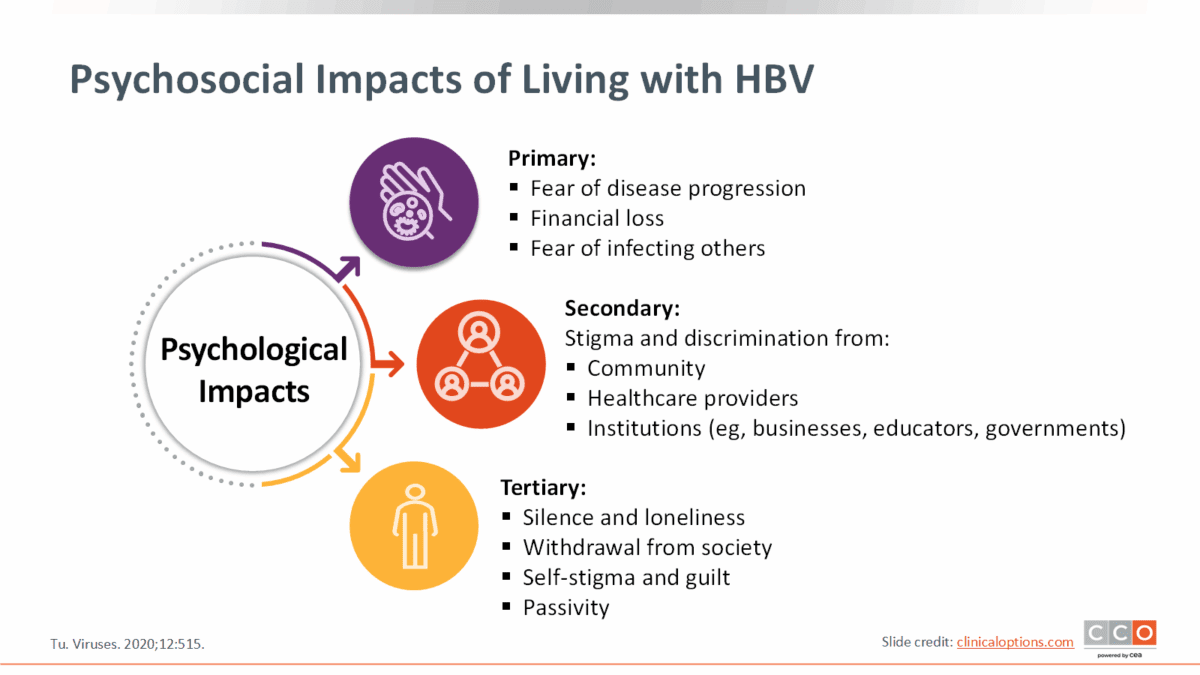

Pointing to psychosocial effects of living with hepatitis B, Dr Wang said, “We think of hepatitis B virus as a liver disease, but it affects multiple dimensions of a person’s life. The psychosocial burden on people living with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) can actually be greater than the physical manifestations from the disease.

“Many individuals worry a great deal about developing liver cancer or transmitting the virus to others, and it can impact how they see themselves and how they interact with others. CHB becomes a stressor, and many feel they cannot be in a relationship because of having to divulge their status.”

Dr Wang emphasised the value of empowering people with CHB to be a actively involved in their treatment choices and urged heath care providers to offer treatment to all people living with CHB, and to evaluate risks and benefits individually and use shared decision-making when discussing therapy.

We have all the tools to get HBV eliminated by 2030, but it requires us to get more care to more individuals with chronic hepatitis B

“It is important to let patients know that there is a decision to be made about treatment and invite their participation. We need to ask what is important to them, offer them options, and then come up with a plan together,” she said.

“Some patients want to be proactive and receive treatment even if their risk may be low, whereas there may be others who prefer close monitoring over treatment.

“For those who start treatment, adherence must be emphasised as there is a risk of hepatitis flare if treatment is stopped. Although many people discontinue treatment and remain asymptomatic, there is a small percentage of people who experience much worse outcomes, including fulminant liver failure.”

Dr Wang also stressed the need to counsel patients that whether or not they’re on treatment, chronic hepatitis B is a dynamic disease that requires regular monitoring and liver cancer screening, adding that elimination of hepatitis B by the WHO target of 2030 is possible.

“We have all the tools to get HBV eliminated by 2030, but it requires us to get more care to more individuals with chronic hepatitis B. We should not be delaying HBV treatment as we wait for a functional cure; we should be doing what we can now – diagnosing and providing HBV treatment to those in our care.”

Content for this article used with permission from Clinical Care Options.

Last updated 28 November 2025

More from:

Enjoyed this article? Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish new stories.

Subscribe for Updates