Unlike a number of other viruses, hepatitis C (HCV) is only naturally found–and able to replicate–in humans and, to a lesser extent, chimpanzees. This has proven to be a major stumbling block in researching cures for the virus in the search for an effective vaccine, because the usual pharmaceutical approach when developing medications is to test heavily on animals before going to human trials.

Mice are commonly used in efficacy and safety trials for most new pharmaceuticals, and so developing a way to get hepatitis C to grow in mouse cells would speed up the development of any future vaccines and treatments.

In order to understand why the virus cannot infect mice and to enable the development of new animal models, researchers at the TWINCORE infectious disease research centre in Germany have created a variant of HCV that can infect mouse liver cells in vitro. They have now published their work in the journal JHEP Reports.

The development of a (HCV) vaccine has also failed so far because we did not have an animal model

In her previous research, Dr Julie Sheldon, a scientist at working at TWINCORE, had already investigated HCV variants that were better adapted to human cell cultures, which means being able to experiment on human cells without actually experimenting on any human beings. “Here, we now describe the first HCV variant that can infect mouse liver cells and also replicate there,” she explained of this new study.

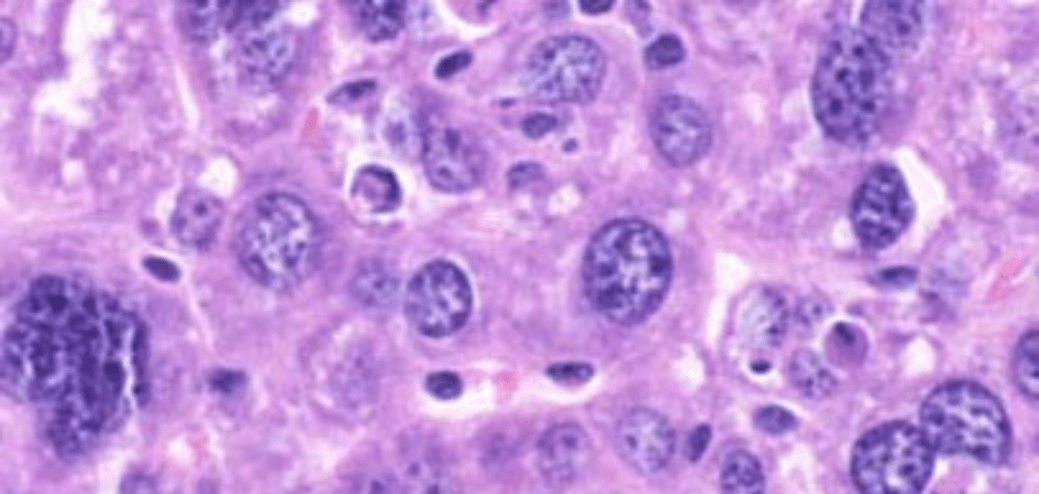

To achieve this, she and her colleagues took advantage of a characteristic of HCV–it’s ability to mutate into many various genotypes. “HCV is an RNA virus that generates a very large population of variants due to a high rate of replication and mutation,” says Sheldon. “This diversity allows the virus to quickly adapt to changing environmental conditions and enabled us to adapt the virus to infect mouse cells.”

“The new HCV variant replicates very efficiently in liver cells isolated from mice,” says Sheldon. A total of 35 changes in the virus’ proteins were needed to allow this, which is about 1 per cent of the hepatitis C’s DNA. The modified virus is still 99 per cent identical to the original virus, but will open up completely new possibilities for research.

“This has brought us a major step closer to developing a mouse model for HCV,” noted Professor Thomas Pietschmann, Director of the Institute of Experimental Virology at TWINCORE. “The development of a vaccine has also failed so far because we did not have an animal model. Thanks to our new findings, this is now within reach.”

Last updated 15 May 2025

More from:

Enjoyed this article? Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish new stories.

Subscribe for Updates