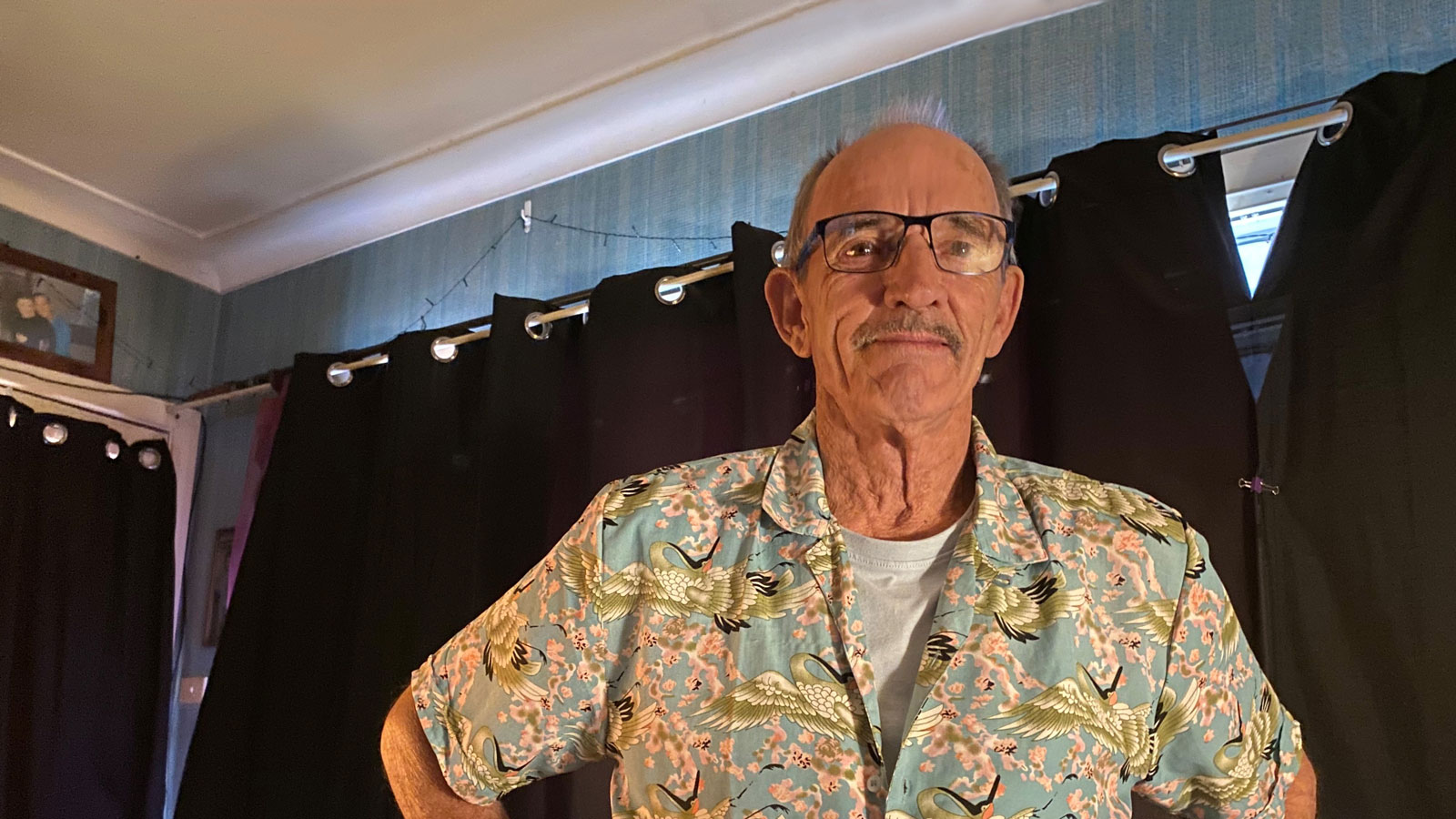

Adrian Hicks wants to shout out to the world: If you have hepatitis B, don’t ignore it… do something, your life may depend on it! Adrian lives with not one but two hepatitis viruses: hepatitis B and hepatitis D.

The hepatitis D virus (HDV) – sometimes known as hepatitis delta virus – is a virus that needs the hepatitis B virus to survive in the human body. In Australia, people diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B are not automatically tested for hepatitis D even though having hepatitis D puts additional burden on the liver often with serious health outcomes.

Adrian was diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B in 1980, and after decades of being told his liver was ok, discovered in 2020 that not only was his liver not ok, but he had hepatitis D as well… and liver cancer.

“I was in the hospital within a few days for a liver resection,” he recalled. The scariest part of it all was the fact that the discovery of his liver cancer had occurred by chance.

“In 2020, my partner Sal was diagnosed with lung cancer – I went with her to the hospital, and it so happened that I saw it had a liver clinic and decided to go and poke my nose around.

“I walked in without an appointment or a referral, but they booked me in anyway, for a test and CT scan. Ten days later I was at the Princess Alexandra Hospital having a part of my liver removed… it happened so quickly.”

I always thought I was ok, once I wasn’t yellow anymore.

Up to that point, Adrian had thought he was one of those who has hepatitis B but remain healthy, so-called healthy carriers – a discredited concept held commonly in decades past.

“I always thought I was ok, once I wasn’t yellow anymore. My sister took care of me when I had the initial symptoms but after those subsided, everything seemed normal,” he said. He had regular blood test that had seemed to indicate his liver wasn’t damaged… until that serendipitous drop-in to the liver clinic in 2020.

“They told me I had liver damage, cirrhosis and liver cancer. I was told I also had hepatitis D and that was what caused further liver damage.”

The prevalence of hepatitis D in Australia is unclear as there is no automatic testing (also known as reflex testing) for hepatitis D provided to people living with chronic hepatitis B. Studies such as the statewide HIDE-SA in South Australia, are currently being conducted in Australia to improve detection of hepatitis D.

For Adrian, finding out that he had another form of hepatitis on top of hepatitis B was a surprise and finding out about the liver damage that had occurred as a result was a shock, albeit in a way tempered by gratitude.

“It was a shock – of course – but it could’ve been worse. If not for that visit, I wouldn’t be here right now,” he said.

He had to travel to Brisbane for the operation. That was 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic; Sal went through a long 15-day application process, getting letters from the hospital, specialist and so on, before she could join Adrian who was still in the hospital, to support him through his six-week recovery from the surgery.

Adrian is now on daily injections of the drug bulevirtide to suppress the hepatitis D, entecavir tablets for hepatitis B, and is monitored regularly.

There is an underlying anxiety about what will happen next. “The liver clinic rang the other day, about some lesions. They have put me on the transplant list, but I’d always been a little unsure about transplants,” he said.

“There are many hoops to jump through, it’s a lengthy procedure and I need to be within two hours of the hospital which could mean relocation as I’m currently two and a half hours away.

People think you got it because you were alcoholic or got hep B because you were promiscuous, or injected drugs…

“But my liver specialist is the best. I am very grateful to him and I trust him, so we’ll just take it a step at a time.” Meanwhile, Adrian will be undergoing a special chemotherapy process known as transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) to shrink the cancer. TACE directs the chemotherapy drug straight to the cancer cells in the liver via the hepatic artery, the main vessel from which liver tumours get their blood supply.

He is philosophical about his personal situation (Sal calls him “a real trouper”) taking it one day at a time – both he and Sal dealing with their respective treatments – and living life.

Over and above that however, Adrian wants to do everything he can to raise awareness about hepatitis B, hepatitis D and liver cancer which he refers to as an “unpopular cancer” because there is so much judgement associated with it.

“People think you got it because you were alcoholic or got hep B because you were promiscuous, or injected drugs… so there’s less sympathy and interest in supporting and funding it,” he said. “But it is important to give it attention because it is a cancer that can be prevented, with vaccinations, proper monitoring for those with chronic hep B, and hep D reflex testing on people living with hepatitis B.

True to his word, Adrian has joined a Hepatitis Australia working group on hepatitis D, sharing his lived experience and contributing to the group’s goal of developing resources and engagement approaches to raise awareness among at-risk communities.

“I have liver cancer. I accept that, but I want to help raise awareness and do what I can to stop the same thing happening to others. I like that slogan – Hep B Stops with Me.”

To find out more about the hepatitis D working group, email Tuva at Hepatitis Australia. If you live with hepatitis D and would like to share your story, drop Community News a line at .

Last updated 28 November 2025

More from:

Enjoyed this article? Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish new stories.

Subscribe for Updates