Part of a liver from a genetically engineered pig has been transplanted into a living human recipient, who then survived a further six months before dying from repeated upper gastrointestinal hemorrhages.

The research was reported in a new study published in the Journal of Hepatology, led by Dr Wenjie Zhang and Dr Beicheng Sun. It shows that genetically engineered pig livers can support key hepatic (liver-related), metabolic (breaking down food for the body to use) and synthetic (making new chemicals for the body) functions in human beings for extended periods of time. It also shows the difficulties in making this work for the length of a full human lifetime.

Around the world, there are thousands of people who die every year while waiting for organ transplants, due to the limited supply of viable human organs. In the researchers’ home nation of China, for example, hundreds of thousands of people experience liver failure annually, yet only around 6,000 people received a liver transplant in 2022. This pioneering research offers a potential new avenue to bridge the alarming gap between organ demand and availability.

The recipient of the genetically engineered pig’s liver was a 71-year-old man with cirrhosis and liver cancer which had been caused by long-term hepatitis B. He was not eligible for a human liver transplant, nor would he have been helped by a liver resection, where a diseased part of the liver is removed.

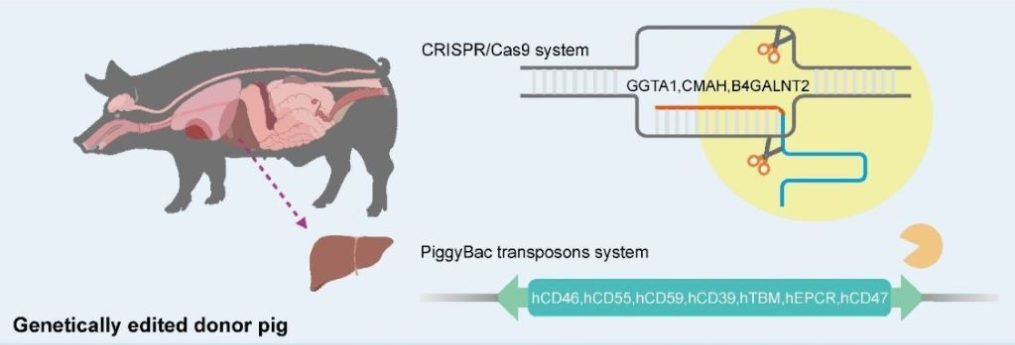

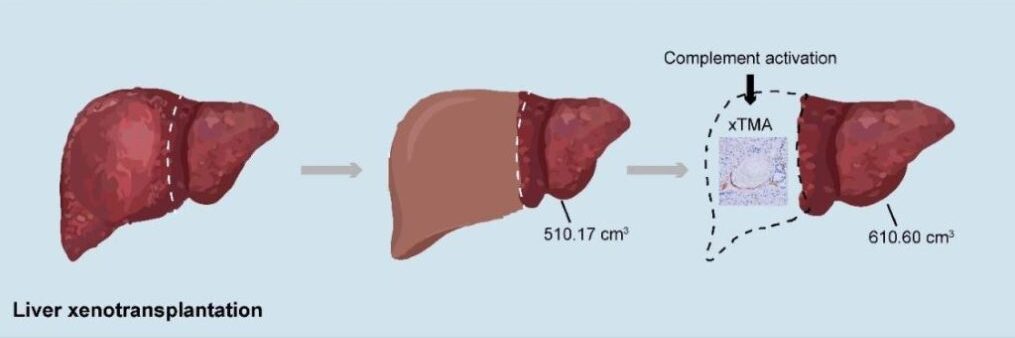

The “donor” (the word is used uneasily, since the pig could obviously not provide consent) was a miniature pig with edits to 10 of its genes, designed to increase compatibility with the human recipient by removing immune system triggers and improving blood coagulating after surgery. Part of the human patient’s liver was removed and replaced with a graft consisting of the larger part of the pig’s liver.

For the first month after surgery, the xenotransplanted (meaning ‘transplanted from another species’) liver functioned effectively, producing bile and synthesizing coagulation factors, with no evidence of rejection or infections. However, on day 38, the new liver was removed following the development of thrombotic microangiopathy, which is the formation of potentially lethal blood clots in the body’s smallest blood vessels, caused by the transplanted liver.

The patient was then treated successfully for the clots, and lived for a further four months, but then later experienced repeated upper gastrointestinal hemorrhages, and passed away 171 days after the initial surgery.

“This case proves that a genetically engineered pig liver can function in a human for an extended period,” explained Dr Beicheng Sun, the lead investigator. “It is a pivotal step forward, demonstrating both the promise and the remaining hurdles, particularly regarding coagulation dysregulation and immune complications, that must be overcome.”

Dr Heiner Wedemeyer, hepatologist and co-editor of the Journal of Hepatology, agreed. “This report is a landmark in hepatology. It shows that a genetically modified porcine liver can engraft and deliver key hepatic functions in a human recipient. At the same time, it highlights the biological and ethical challenges that remain before such approaches can be translated into wider clinical use. Xenotransplantation may open completely new paths for patients with acute liver failure, acute-on-chronic liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma. A new era of transplant hepatology has started.”

Of course, even if it is made to work perfectly, xenotransplantation still brings with it a number of ethical and medical issues, including the risk of animal-human disease spillover, all of which need to be carefully considered as research continues.

Last updated 28 November 2025

More from:

Enjoyed this article? Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish new stories.

Subscribe for Updates