As the coronavirus spread globally in 2020, and people all around the world began to be uncomfortably familiar with RAT tests and PCR tests, NSW historian Michelle Bootcov realised her in-progress PhD on the history of hepatitis B was also a history of the medical discoveries underlying the world’s ability to respond to the pandemic.

“Both the rapid antigen tests (RAT tests) and the variant sequence analysis (PCR tests) that became common knowledge to the general public during COVID, had historical antecedents in hepatitis B research of the 1960s to 1990s,” explained Dr Bootcov, who received her doctorate from the University of NSW in 2024.

Hepatitis B was a medical emergency in the 1960s, because the increasing use of blood transfusion was accompanied by an increasing incidence of post-transfusion hepatitis. “Although the incidence was low in Australia, elsewhere it was as high as 20% to 50%, particularly for multi-unit transfusions from paid donors” Dr Bootcov said.

“This was especially problematic because HBV infection is frequently asymptomatic, and at that time there was no way to rapidly detect the virus in donated blood, and thus prevent transmission.

“In fact, there was no way to rapidly diagnose any viral infection. Laboratory diagnosis took so long that the saying was that the patients were dead or discharged from hospital before the results came back.”

Without a detection test for the virus, the extent of hepatitis B infection was unknown, and only identified in asymptomatic donors when their blood recipients developed post-transfusion hepatitis, at which point it was obviously far too late to prevent transmission.

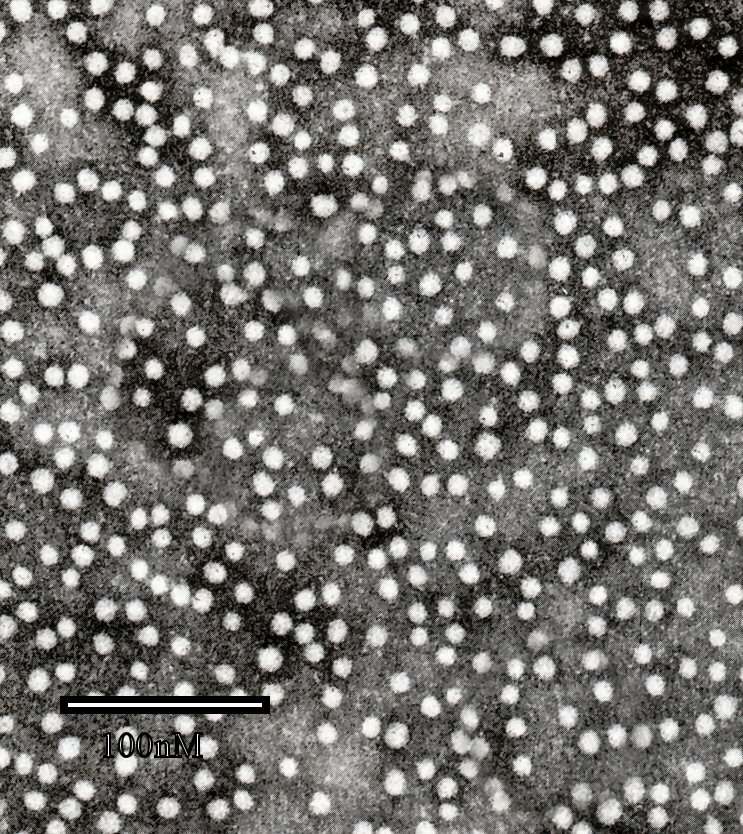

After decades of futile research by virologists and haematologists, in the late 1960s there was a breakthrough: a test that could detect an antigen associated with the virus. An antigen is a substance that causes the body to make an immune response against it. The presence of one particular antigen in blood reliably indicated hepatitis B infection, and improvements to those antigen testing techniques soon reduced the time to get test results to just a few hours. This was an essential requirement for the use of donor blood products. And this test was the first rapid antigen test for mass screening for a virus anywhere in the world.

The antigen in those first hepatitis tests was a protein on the surface of the hepatitis B virus, and initially it was called “the Australia antigen” because the blood in which it was discovered came from an Indigenous community in Central Australia.

“The Australia antigen was serendipitously identified in the mid-1960s through genetics enquiry. Within a few years, following a series of research twists and turns and two hepatitis B transmission events that caught the attention of alert scientists, it became clear that the Australia antigen was not the product of a human gene, it was a viral protein,” said Dr Bootcov.

The method used in genetics to identify the Australia antigen became the method by which hepatitis B infection could be detected rapidly in donor blood. “This discovery transformed blood transfusion services’ management of donor blood, and the high demand for those tests fuelled the establishment of the viral diagnostics industry,” explained Dr Bootcov. Reliable testing also revealed the true and frightening extent of hepatitis B infection. In some countries it was hyper-endemic.

These improvements in blood donor testing paved the way for blood management when HIV/AIDS emerged in the 1980s.

Hepatitis B was also amongst the first viruses to be fully sequenced and its variants analysed. This is a type of analysis that became all too familiar across the world during the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic, when Delta, Omicron, and other variants were discovered, traced and tracked.

“Looking back to December 2019 and the emergence of an unfamiliar pneumonia in Wuhan, China, it is amazing to recall the speed with which the coronavirus was isolated, and its genome fully sequenced and published,” noted Dr Bootcov.

“Soon rapid antigen tests (RATs) could be conducted at home within 15 minutes, [and] PCR and sequencing was so fast that a result could be texted within hours, and viral variant transmission tracked in real time. Few paused to marvel at the magnitude of that scientific possibility!”

“It had come to be expected. And much of it was thanks to the technologies that emerged through research that began with the hepatitis B virus and its Australia antigen.”

Last updated 30 October 2025

More from:

Enjoyed this article? Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish new stories.

Subscribe for Updates