The Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) has recently rejected an application for a new drug, bulevirtide, to be available at subsidised rates for treatment of hepatitis D, despite submissions from community and health organisations.

Hepatitis D is the most severe form of viral hepatitis carrying with it a 70–80 per cent risk of cirrhosis in five to ten years, and liver cancer within ten years. It is uncommon in Australia, and only infects people already living with hepatitis B, putting them at a significantly higher risk of serious disease and death. About a quarter of people who develop cirrhosis from hepatitis D will die of liver failure.

The hepatitis D virus can only live in people already infected with hepatitis B, because it doesn’t have its own cellular “machinery” for reproduction, and relies on making use of that provided by the cells of hepatitis B. It is the smallest known pathogenic virus in humans.

Hepatitis D is spread when infectious body fluids (blood, saliva, semen and vaginal fluid) come into contact with body tissues beneath the skin (for example, through needle punctures or broken skin) or mucous membranes (the thin moist lining of many parts of the body such as the mouth, throat and genitals). Hepatitis B vaccination will prevent both hepatitis B and hepatitis D.

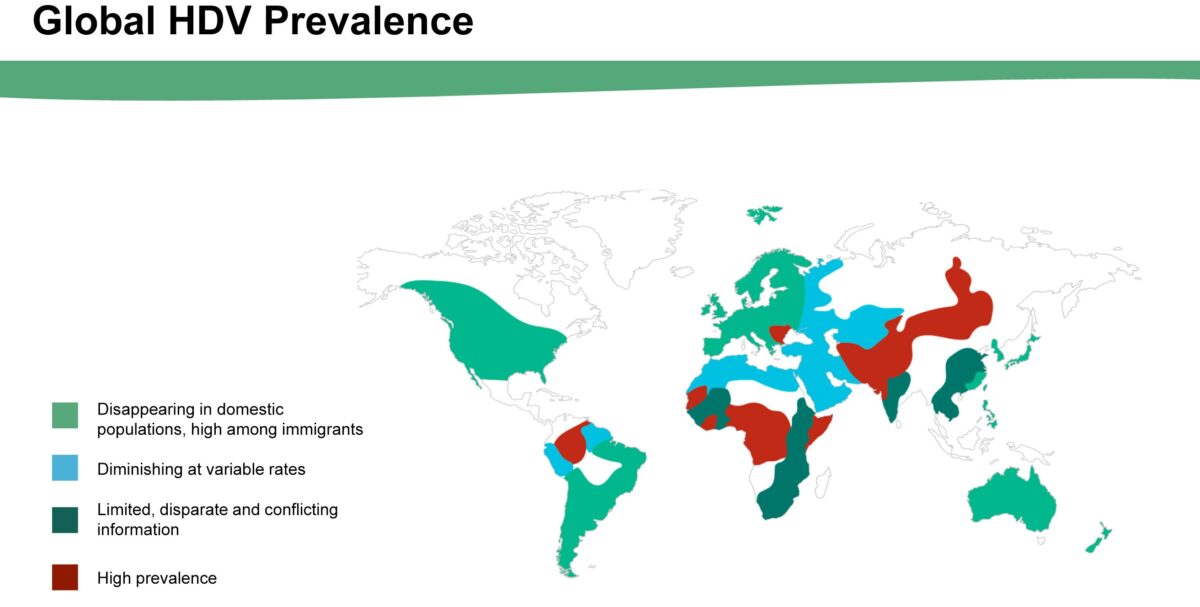

In Australia, hepatitis B prevalence is highest among migrant communities from countries or regions of higher prevalence, as well as First Nations communities. It is estimated that there are around 12,000 South Australians living with hepatitis B. From 2020 to 2024 an average of 232 cases of hepatitis B and seven cases of hepatitis B and D co-infection were notified per year in South Australia.

We were significantly behind in our efforts to reach the 2022 national hepatitis B targets for diagnosis and linkage to care, and also behind in reaching 2030 global elimination targets. It is likely that hepatitis D is also under-diagnosed.

The current treatment options for hepatitis B/hepatitis D chronic infection are limited, and need to be carefully discussed with a person’s treating doctor.

A new targeted treatment, bulevirtide, has been approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration for use in Australia. It has a much higher efficacy and is more well tolerated than the current treatment options. Buleviritide works by blocking the hepatitis D virus’s access to regenerated liver cells, letting the immune system eliminate infected cells. This can result in prevention of viral replication, and subsequent reduction in inflammation and associated liver damage. However, Buleviritide is not currently approved for subsidised access through the PBS.

Considering the fact that those most affected by hepatitis B—and therefore vulnerable to hepatitis D—already face barriers to healthcare, removing the cost barrier to accessing this more effective treatment is surely vital to managing this deadly form of hepatitis. Its rejection for listing on the PBS is no doubt disappointing to those in the sector who have lobbied for it.

The peak body for health professionals in the field, ASHM, recommends that people living with hepatitis B automatically receive a hepatitis D antibody test—reflex testing is a straightforward and simple way to do this—and anyone testing positive should then have a hepatitis D PCR test to confirm active infection and inform clinical care. For those who commence treatment, twice-yearly monitoring via hepatitis D PCR tests is then extremely important.

Unfortunately, the cost of the medication itself is just one of the barriers to clinical management faced by people living with hepatitis D. We also need to remove the costs associated with the hepatitis D PCR tests, which are an essential component of determining eligibility to commence treatment, and to monitor the clinical benefits, and consequently the duration, of treatment.

Hepatitis SA has joined the call for action on hepatitis B and D. Improving access to testing and guideline-based care including subsidised, effective treatments is key to improving outcomes for people living with hepatitis B and D co-infection.

See our special issue on Hepatitis D here.

ASHM (2020). National Hepatitis B Testing Policy v 1.2, Commonwealth of Australia, Barton. ACT. https://testingportal.ashm.org.au/files/ASHM_TestingPolicy_2020_HepatitisB_07_2.pdf

Last updated 16 May 2025

More from:

Enjoyed this article? Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish new stories.

Subscribe for Updates