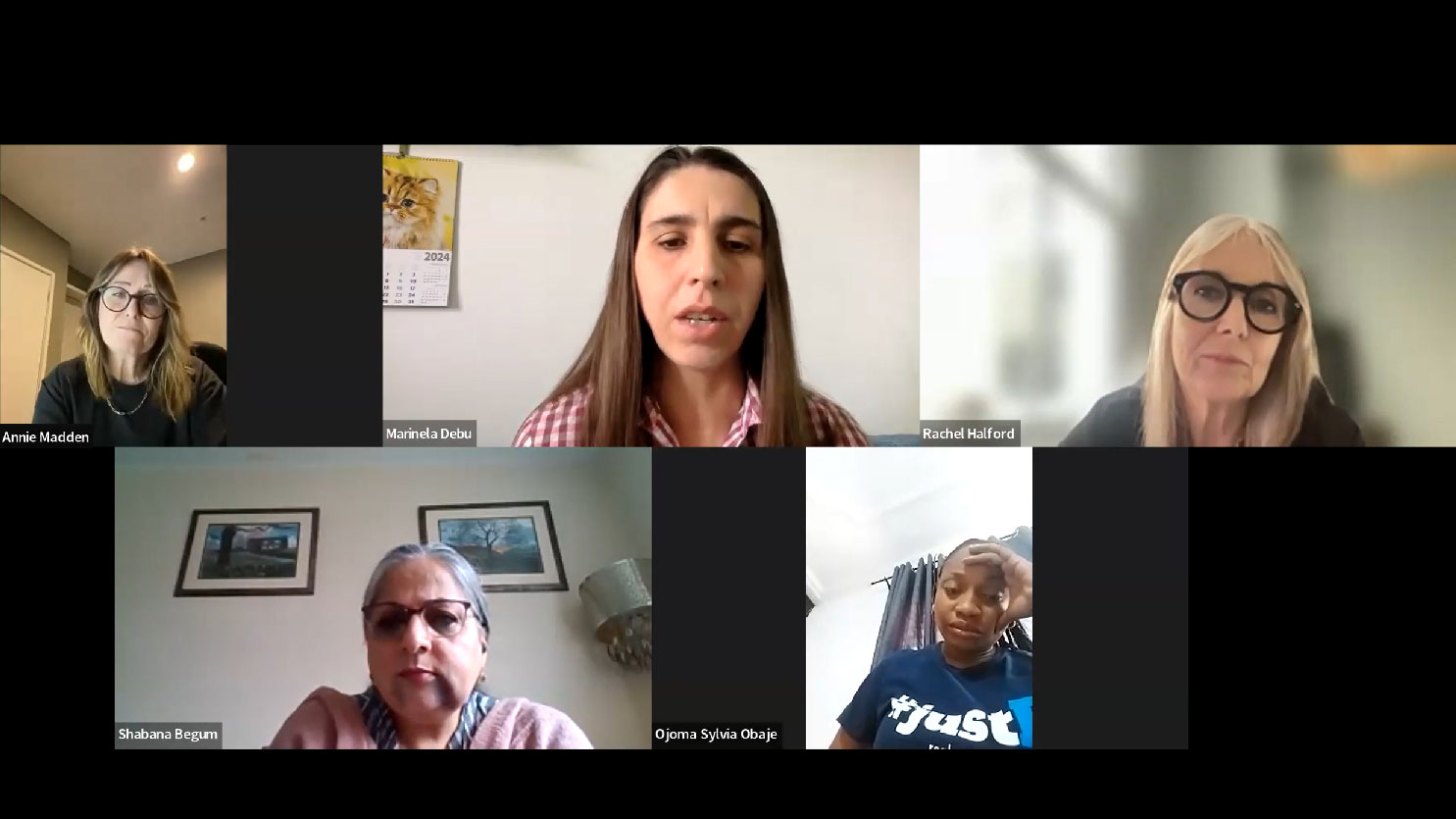

Around the world, women living with hepatitis face barriers to getting care and treatment, beyond those faced by their male counterparts. This was the clear message from an international panel of women leaders from the hepatitis-affected community at a recent World Hepatitis Alliance forum to mark International Women’s Day 2024.

Speakers from Nigeria, Romania, Australia and the UK South Asian community, grappled with questions around supporting women who live with viral hepatitis. They spoke from their own lived experiences as well as their work in leading viral hepatitis organisations in their communities.

Information and Access

Marinela Debu, President of Romanian Association for Patients with Liver Disease, said many women don’t know that they can get tested for hepatitis free if they are pregnant, but apart from lack of information about available health services, women tend to put themselves last. “In a family, if a man has hepatitis and woman has hepatitis, the woman will think it’s important to make sure her man is okay and healthy, then maybe will look at herself,” she said.

“In rural areas, it is much more difficult to get access to health services with hospitals 15, 20, 100 kilometers away. Women have no time to look after themselves; they have to work the land and look after the family.

“Even if women can get access to testing, what is the next step? Doctors can prescribe therapy if you’re insured but if you want them to carry on life as usual, they must know the correct information about transmission so they can protect [and stand up for] themselves.”

She said because of ignorance, women are often ostracised when they’re diagnosed with hepatitis B. She has seen blame and discrimination within families lead to divorce with emotional consequences for the children and the mothers.

…women’s social position, plus limited access to education and information means they don’t know about health services, or they could be exploited by unscrupulous service providers.

She recalled a distraught woman who was diagnosed with hepatitis B, who didn’t know what to do about her husband because he was “accusing her of giving hepatitis to their future children”. Marinela spent hours helping the woman explain to her family what she needed to do, to understand it was not “the end”, and that she won’t give hepatitis to their children if she discussed with the doctor and took the necessary steps to reduce chances of mother-to-child transmission of her hepatitis B.

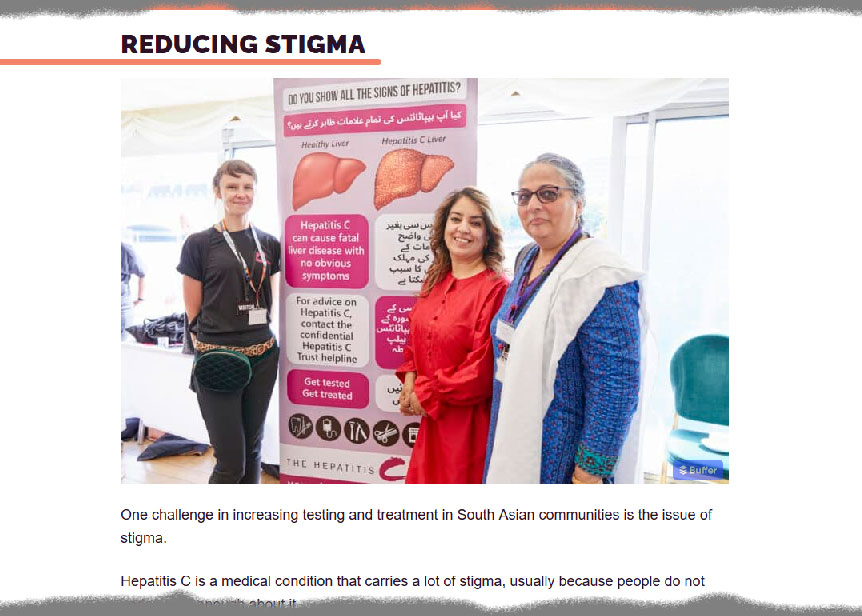

Shabana Begum, National South Asian Project Coordinator at The Hepatitis C Trust, UK, said women’s social position, plus limited access to education and information means they don’t know about health services, or they could be exploited by unscrupulous service providers.

“For example, in Pakistan even if women do have access to healthcare, they need somebody to go with them, and they need someone to explain things to them. One of my cousins actually got treated for hepatitis a couple of years ago. She told me her story… she did the three months [hepatitis C] treatment on the new medication; at the end of the three months, the doctor said ‘there’s still a bit of hep C left in you, why don’t we, just to be on the safe side, do another three months?’ She didn’t have to do that at all, but because she didn’t have the education and the knowledge, she was conned into doing another three months of treatment and had to part with more money,” she said.

…the medication, even if available, could be unaffordable and the situation would be even worse with home births.

Annie Madden, Executive Director of Harm Reduction Australia, pointed to the difficulty of getting any funding for women-specific services, for women who inject drugs even though women are known to be more at risk of hepatitis C transmission because they are usually last in line for the needle, something that’s reflected in the higher hepatitis C infection rate among female prisoners compared to male prisoners.*

Ojoma Sylvia Obaje, Hepatitis B Foundation Storyteller from Nigeria, said many women in developing countries don’t know they have hepatitis B until they are tested when they’re pregnant, and when diagnosed, they may not have access to the necessary treatment to protect their baby. The medication needed might have to be transported from great distance in cool packs and may affect the efficacy of the drugs. That also means the medication, even if available, could be unaffordable and the situation would be even worse with home births.

What Women with Hepatitis Need

Panelists agreed that key strategies needed to meet the urgent needs of women living with hepatitis B and C, are information and education, women-specific services, and peer support networks.

“It comes back to education,” said Shabana. “We need to get the information out there through TV, radios like we do on World Hepatitis Day, information targeted at women targeted for them and their children, information in different languages that they can actually understand.”

She said, a booklet about hepatitis C in English and Urdu, which the Hepatitis C Trust took a year to put together was very well received by the South Asian community – “going like hot cakes”.

“Ideally if something like that can be translated into other languages, it would give women the information and at least they can make their own decisions. It’s really essential that they are educated because they don’t have that education, they get put on the back burner.”

…when I was educated by my lovely nurse and learnt more about hepatitis transmission routes, I was able to overcome that and think, okay – I’ve not done anything wrong.

Sylvie would like to see public education campaigns with stickers, billboards everywhere, and social media, to help people “come to the realisation that this disease is like every other disease and is not a death sentence. You can have hepatitis and live a normal life”.

Education and information empower women to stand up to stigmatisation and finger pointing. “When I was diagnosed with hepatitis C I was stigmatized,” said Shabana. “People close to me, stepped away… it was like a death sentence, and it wasn’t nice. But when I was educated by my lovely nurse and learnt more about hepatitis transmission routes, I was able to overcome that and think, okay – I’ve not done anything wrong. So, I think I can help other women going through the same thing.”

Shabana believes normalisation is an important part of removing stigma. “Of late, I’ve been trying very hard to normalise hepatitis C,” she said. “People are okay talking about diabetes, getting the blood test, BMI done and everything… can we join that with everything else? TB test, HIV, antibody tests. What’s the difference? There’s not much difference.

“People come up to me and ask if we are testing for diabetes, and I said no we’re actually testing for hepatitis C and in some cases, hepatitis B and HIV as well. Have an open conversation instead of being in a closed room. What I’ve actually done with the South Asian Community is have tests done openly so there are lines and lines of people… people waiting, looking on… oh what’s happening they’ll ask, and you explain it’s a hepatitis test, oh that’s all right, we’ll get it done.

…she stands there proudly to say it’s okay [that] you know, I have no problem standing here saying I have hepatitis.

“If you go to a mosque on a Friday, there are hundreds of people there even if they don’t want to get tested, they’ll walk away some information. People that do get tested are quite happy and they’ll pull in other members they know , friends, colleagues: we are getting tested, why don’t you get tested as well.

“Normalising hepatitis B and C testing, that it’s ok to get tested within community settings – it’s very similar to what Marinela was saying, she stands there proudly to say it’s okay [that] you know, I have no problem standing here saying I have hepatitis.”

Mutual Support – Empowerment

Education was important to help women with hepatitis B understand and feel better about their situation, said Marinela. “When I found I had hepatitis, I lost some of my friends. If we want to lose stigmatisation, we must discuss it. If you don’t overcome stigma, you can’t solve the physical impacts, because if you don’t solve the problem, you can lose people important to you.” She said more and more people are being diagnosed, and if people talk about hepatitis openly as part of normal daily conversation, they give each other the power to talk about what they are facing and help each other.

While women-specific health services will help to reduce barriers for women to get the healthcare they need, Annie pointed to the “appalling reality” that it is very difficult to get donors, funders and governments to be interested in women-specific services, particularly in relation to viral hepatitis. “That has been my experience in various countries and regions, not just Australia,” she said.

…So that we know that it is not the end of the world – we can thrive, live like every other person…

A suggestion was made to push for a women-focus theme or activity in the 2024 World Hepatitis Day campaign, to raise the profile of issues faced by women living with hepatitis.

It was also pointed out that mutual support was crucial in helping women work through their diagnoses, find answers to their questions and take care of their mental and physical health. One suggestion was for a WhatsApp group for women to come together every single day, not just one day a year on International Women’s Day.

“If you’re woman, and a mother, you must have the courage to discuss your disease,” said Marinela. “Encourage people to vaccinate – it is very important. Be open to discuss with your husband, your mother, family. Sometimes you could be in for a big surprise, someone in your family might get tested positive and you have saved their life.”

For Shabana, education is key. “From my experience, it is the only way to reduce stigma. It’s up to you to do that, not anyone else. We have power to empower other ladies as well to participate, get educated, tested and treated and raise awareness everywhere.”

Sylvie wants “women all over the world to hear our voices to push this cause so that every woman, every child everywhere [with hepatitis] would live a normal life. So that we know that it is not the end of the world – we can thrive, live like every other person, that we are not less of a human because we are diagnosed with the virus. That is what I want – yes.”

* https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/prisoners/health-australia-prisoners-2018/summary

Last updated 3 May 2024

More from:

Enjoyed this article? Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish new stories.

Subscribe for Updates