The World Hepatitis Summit has called on governments to put words into action and take concrete steps to reduce the impact of viral hepatitis. Participants at the Summit’s final sessions expressed anger at political leaders over their disregard for the thousands of hepatitis deaths every day, and at their lack of action in moving towards hepatitis elimination despite signing up to the World Health Assembly’s hepatitis elimination goal in 2016.

Numerous speakers and delegates from the floor pointed to the alarming number of hepatitis deaths, presented in the WHO Global Hepatitis Report released at the Summit two days before. The 1.3 million deaths from hepatitis B and hepatitis C each year were, they said, totally unacceptable because effective prevention and treatments are available for these diseases.

…what hepatitis advocates had been doing for so long does not work …data is still showing that people are dying. Let’s do something different!

The Global Hepatitis Report 2024 revealed that despite a decline in new hepatitis infections, hepatitis deaths had continued to climb, with hepatitis B accounting for 83 per cent of the deaths. Panelists at the “Why we must succeed” session, all of whom have lived experience with hepatitis, spoke of the sadness – and anger – they felt, knowing that those deaths were preventable.

Some, like World Hepatitis Alliance (WHA) past-President and community advocate, Danjuma Adda, said the hepatitis community had been “too quiet”. “We need to knock on doors… and shake the tables,” he said, adding that what hepatitis advocates had been doing for so long “does not work” as data is still showing that people are dying. “Let’s do something different!”

WHA board member, Dee Lee, echoed the sentiment saying hepatitis advocates – even those competing for the same funding – need to work together to get decision-makers’ attention, knock on the doors of parliament members or maybe, metaphorically, “just try to burn down something”.

Speakers and delegates from the floor point to the many medical advances in the field in the last 15 years – the increase in drug options for hepatitis B management, immunoglobulin for newborn babies of mothers with hepatitis B, and the “miraculous” direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C. Despite these clinical tools people continue to die from hepatitis.

Speaking from the floor, Dr Garaba Danjuma, from Taraba, Nigeria, said despite his state’s health authority holding weekly meetings to look at data for HIV, viral hepatitis, TB and Malaria, they “truly don’t give very much attention to viral hepatitis” – something he aims to change going forward.

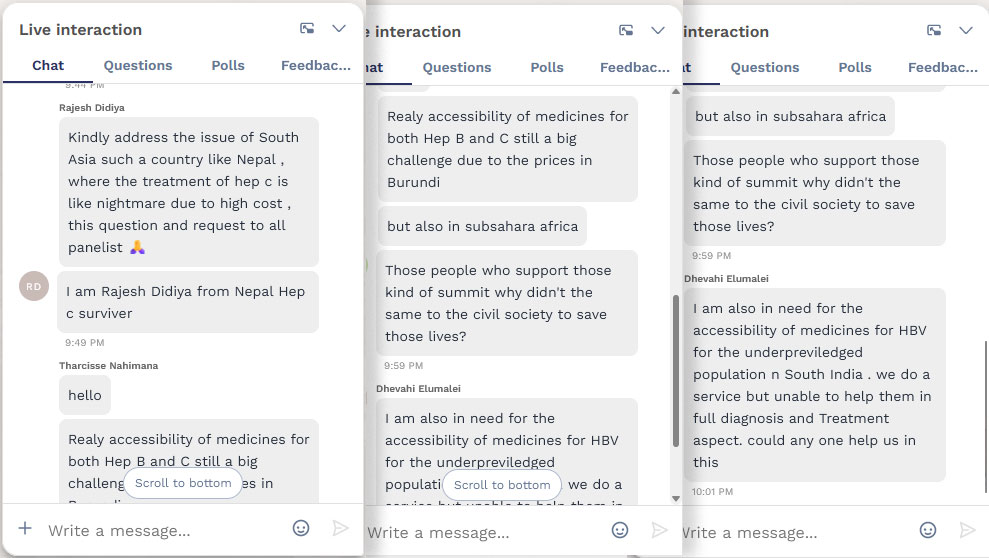

Delegates online called on supporters/funders of the Summit for help in their home countries and regions. “Those people who support those kind of summit why didn’t [they do] the same to the civil society to save those lives?” asked one. Another said: “I am also in need for the accessibility of medicines for HBV for the under privileged population in South India. We do a service but unable to help them in full diagnosis and treatment aspect. Could anyone help us in this?”

One delegate from Nepal, asking speakers to address the “issue of South Asia”, described the hepatitis C treatment there as “a nightmare” due to the high cost. This was echoed by a Burundian delegate who said the issue was the same throughout Sub-Saharan Africa.

Even if I have nothing else, I have my mouth, and I can speak.

While there was anger, there was also optimism. One delegate from India shared his experience in the HIV movement providing secretarial support to parliamentarians, regularly feeding them information and sensitising them to the issues, recruiting 50 MP champions out of 750 parliamentarians, keeping their issue topical and generating discussions in parliament.

Fungisai Siggns, founder of Hepatitis Zimbabwe, likened everyone in the movement to ingredients in a cake. “Everybody is important so we must work together. We must succeed because people are dying, people are sick.” The speaker from Guatemala, Patricia Velez-Moller said, “we will succeed because we must… Fifteen years ago there was no World Hepatitis Day, ten years ago there was no cure for hepatitis C,” she said pointing to advances in community organisation and medical treatment.

Zipporah Achieng from the National Syndemic Disease Council, Kenya, said she would not wait for governments to move, echoing other voices from the floor urging delegates to keep talking about hepatitis when they return to their work and home countries after the meeting. She said advocates need to keep talking about hepatitis every day, to people who are affected by the disease as well as those not. “Even if I have nothing else, I have my mouth, and I can speak,” she said.

She believes that by 2030, hepatitis will be gone, and she won’t be hearing children say, “I have hepatitis” like she had to say when she was a child.

Let’s hope governments and funding bodies hear her.

Last updated 16 May 2024

More from:

Enjoyed this article? Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish new stories.

Subscribe for Updates