In these COVID-focused times, it is worth remembering that there are other viruses out there, active in our community. World Hepatitis Day reminds us that over 226,500 Australians – including over 12,000 South Australians – live with the hepatitis B virus, and the hepatitis C virus still affects the health of 114,000 Australians despite the availability of highly effective Medicare-funded treatments.

While South Australia has done well in treating people with chronic hepatitis C, the rate of treatment uptake has been dropping dramatically; and our state’s hepatitis B clinical care uptake is below national average, and well below the National Strategy target.

Both chronic hepatitis C and hepatitis B pose risks to liver health and consequently, your overall health. While medical researchers grapple with the search for effective treatments and vaccines for COVID-19, here we have two life-threatening viruses where there is a cure for one, and an effective vaccine and clinical management for the other.

We could cure 114,000 Australians of a life-threatening virus in months. Imagine if it were COVID…

… Imagine if it were COVID-19 instead of hepatitis C. The excitement would be enormous. The health benefits of eliminating hepatitis C although different, is just as great, for individuals and the community. Yet little is said of it to the wider public.

Hepatitis C treatment rate declining

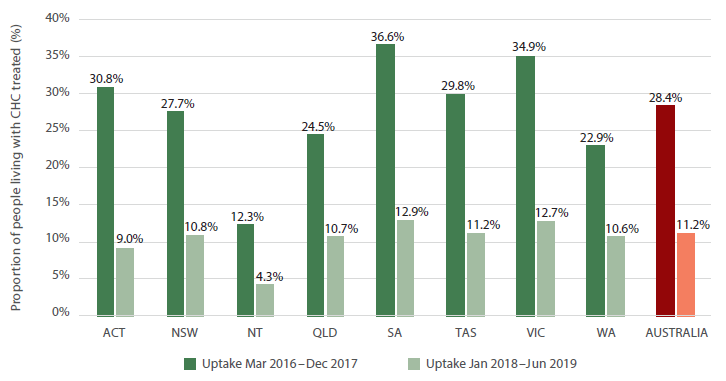

The most recent viral hepatitis mapping report from ASHM shows that South Australia has done remarkably well in treating people with chronic hepatitis C. Between March 2016 when the direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) were introduced on the PBS and mid 2019, half of all South Australians with hepatitis C have been treated. That brought the number of people living with chronic hepatitis C in our state from over 8,934 to 4,419.

If we look further into it, however, we see that while South Australia’s hepatitis C treatment rate of 49.5 per cent is well above the national average (39.5%), the bulk of treatment occurred in the first 19 months of that period. Treatment uptake reduced by more than half, from 36.6 per cent to 12.9 per cent in next 18 months. This pattern is reflected in varying degrees across all states and territories.

Source: Viral Hepatitis Mapping Project National Report 2018-19

If we are unable stop the decline and at least maintain a stable rate of treatment uptake, hepatitis C elimination in Australia by by the WHO target of 2030 may not be achieved.

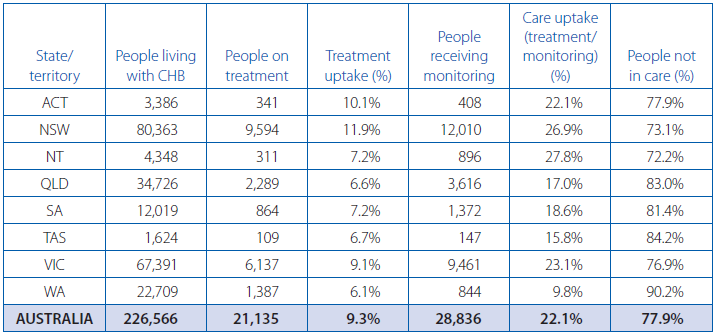

Hepatitis B clinical care below target

The situation is even more challenging with chronic hepatitis B, a condition which is more complex to manage and which is prevalent in diverse communities with different social needs. These communities face barriers to accessing testing and clinical care; barriers different to the mainstream community, and vary for different groups.

Australia’s National Hepatitis B Strategy (2018–2022) aims to have 80 per cent of people with chronic hepatitis B diagnosed, 50 per cent of people with chronic hepatitis B engaged in care and 20 per cent receiving treatment.

In 2018, only 68 per cent of Australians with chronic hepatitis B have been diagnosed, 22 per cent engaged in care (i.e. receiving treatment and monitoring), and a mere 9.3 per cent receiving treatment.

Sadly, South Australia lags behind even those dismal numbers, with 64 per cent diagnosed, 18.6 per cent in care and only 7.2 per cent receiving treatment. Not only that, the number of people in the Adelaide Primary Health Network area who were receiving monitoring while not in care, declined between 2017 and 2018, despite increases at the national level.

Source: Viral Hepatitis Mapping Project National Report 2018-19

Model of Care – the challenge

South Australia’s success in treating people with chronic hepatitis C is due in large part to the very effective system of community based clinics led by a small team of dedicated viral hepatitis nurses. This, coupled with active peer education outreach through clean needle program sites, prisons and community-based organisations, raising awareness about the new DAAs, have helped to reduce barriers to treatment.

This model has worked well in ushering into hepatitis C treatment, those in regular contact with community services. The challenge now is finding those not hearing the message, or those who had been diagnosed so long ago they no longer think about it, as well as the one in five who remain undiagnosed.

There is a need to adapt this model to reaching those who don’t know they have it and “forgotten” hepatitis C cases. Additionally a new model – or a variant of this model – needs to be developed to reach the diverse communities where hepatitis B is more prevalent.

The challenge of raising awareness about hepatitis B and hepatitis C has not been helped by the COVID-19 pandemic which has taken up all of the attention of the public, media and decision-makers – and rightly so.

So, on a lighter note, here is one attempt to ride the COVID coat-tail. For this year’s World Hepatitis Day, the South Australian community have been invited to “Go Viral” and meet COVID-19’s mates – other viruses active in the local community. Participants learn some pithy facts about hepatitis C, hepatitis B, HIV and rhinovirus. They are then invited to test their knowledge in a quiz and enter the draw for an attractive prize of a night away at an iconic hotel in the hills – a relief from the mundanity of staying home.

Such approaches may have to be increasingly adopted in the future as target populations become increasingly harder to reach.

Last updated 3 June 2024

More from:

Enjoyed this article? Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish new stories.

Subscribe for Updates