In the ten minutes it took you to brew your morning cuppa and dunk your favourite bikkie, 25 people died. They were killed by viral hepatitis – part of the 152 people around the world, who die every hour from this treatable, preventable disease.

Locally, about 24 Australians die each week from hepatitis B or hepatitis C. Not as shocking as 25 in 10 minutes but that’s still 1,237 needless Australian deaths each year.

World Hepatitis Day (28 July) is a reminder that Australians cannot afford to rest on our laurels. Although 14 per cent of Australians with hepatitis C have been cured, there are still many, many who need to receive treatment.

Australia’s universal childhood hepatitis B vaccination program will eventually be reflected in less new cases, but our six per cent hepatitis B treatment rate is below the global average (8%) and well below the National Strategy target of 15 per cent. There are 203,000 Australians with hepatitis B who still need to be initiated into regular monitoring and care.

One in five Australians with hepatitis C is not diagnosed, and almost 40 per cent of Australians with hepatitis B don’t know they have it.

In South Australia, hepatitis B treatment rate is only four per cent – below the national average of six per cent.

Clearly, a lot more still needs to be done.

There are 203,000 Australians with hepatitis B who still need to be initiated into regular monitoring and care.

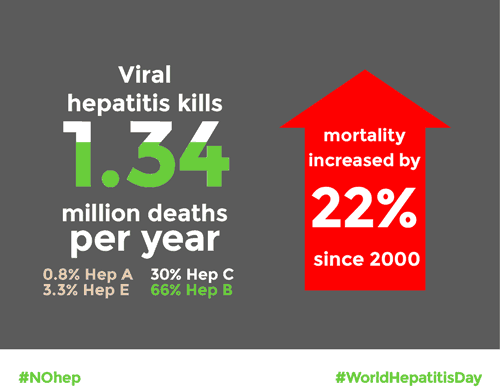

Hepatitis B can be prevented by a safe, effective vaccine and hepatitis C can be cured with success rates as high as 95 per cent. Yet around the world, 1.34 million die from viral hepatitis each year – that’s almost 80 per cent of the South Australian population every year.

Globally, annual deaths due to viral hepatitis rose by 22 per cent from 1.1 million in 2000 to 1.34 million in 2015 and it is expected to further increase. This contrasts with decreases in deaths from HIV, tuberculosis and malaria over the same period. Deaths from chronic hepatitis B complications accounted for 66 per cent of the 1.34 million, with chronic hepatitis C accounting for 30 per cent.

The expected increase in deaths from hepatitis B are due to early childhood infections which occurred before widespread vaccinations started in the 1990s and 2000s. Hepatitis C related deaths are expected to increase because of large-scale transmissions from unsafe health-care procedures and injecting drug use in many middle and low-income countries at the end of the 20th century.

In May 2016, the World Health Organisation (WHO) endorsed the global strategy to eliminate viral hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030, reducing new infections by 90 per cent and deaths by 65 per cent. Led by the World Hepatitis Alliance (WHA) and supported by WHA member organisations world-wide, the campaign was launched on World Hepatitis Day 2016.

WHO has now published its Global hepatitis report, 2017, establishing baseline data for evaluating and tracking progress of the NOhep campaign.

According to the report, there are 257 million people living with hepatitis B and 71 million with hepatitis C. In Australia, four out of ten people with hepatitis B don’t know they have it; worldwide, nine out of ten people with hepatitis B are undiagnosed and four out of five people living with hepatitis C don’t know they have it. In Australia, although hepatitis C diagnosis rate is good, still about one in five don’t know they have it.

There are an estimated 227,000 Australians living with hepatitis C in 2015. New hepatitis C medicines were listed on Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) in March 2016 and the In the 12 months since about 30,000 (about 14 per cent) Australians have been treated for hepatitis C. Universal access to the new drugs means Australia leads the world in treatment rates. For people in many other countries, prohibitive cost keeps the new drugs out of the reach of the majority of people with hepatitis C.

Another 196,000 Australians with hepatitis C need to be reached and treated.

Despite the initial surge in treatment uptake, the number of people in Australia starting treatment is starting to fall off, as easy-to-reach groups complete their treatment. Another 196,000 Australians with hepatitis C need to be reached and treated.

Large numbers of hepatitis B infections go undiagnosed and treatment and monitoring rates of those who are diagnosed remain low. Misconceptions about “healthy carriers” persist. Community education programs on limited budgets are only just beginning, with little promise of continued funding for this crucial work.

Hepatitis is the leading cause of liver cancer in Australia and liver cancer rate in Australia continue to rise as other cancer rates fall. Without on-going effort, the health burden and human cost of viral hepatitis in Australia will continue.

Read full Global Hepatitis Report 2017

Last updated 1 June 2024

More from:

Enjoyed this article? Subscribe to be notified whenever we publish new stories.

Subscribe for Updates