There is a common view that once you start hepatitis B treatment, you will be on it for life. This is changing. In recent years, numerous studies have been done looking into the notion of functional cure for hepatitis B which, when achieved, means therapy can be stopped.

The hepatitis B virus embeds bits of itself in the host cell, allowing it to reactivate and replicate. Current therapy cannot eradicate this remnant of the virus – known as the covalently combined closed DNA (cccDNA). For complete cure to happen, the cccDNA must be eliminated, not merely silenced.

What is functional cure?

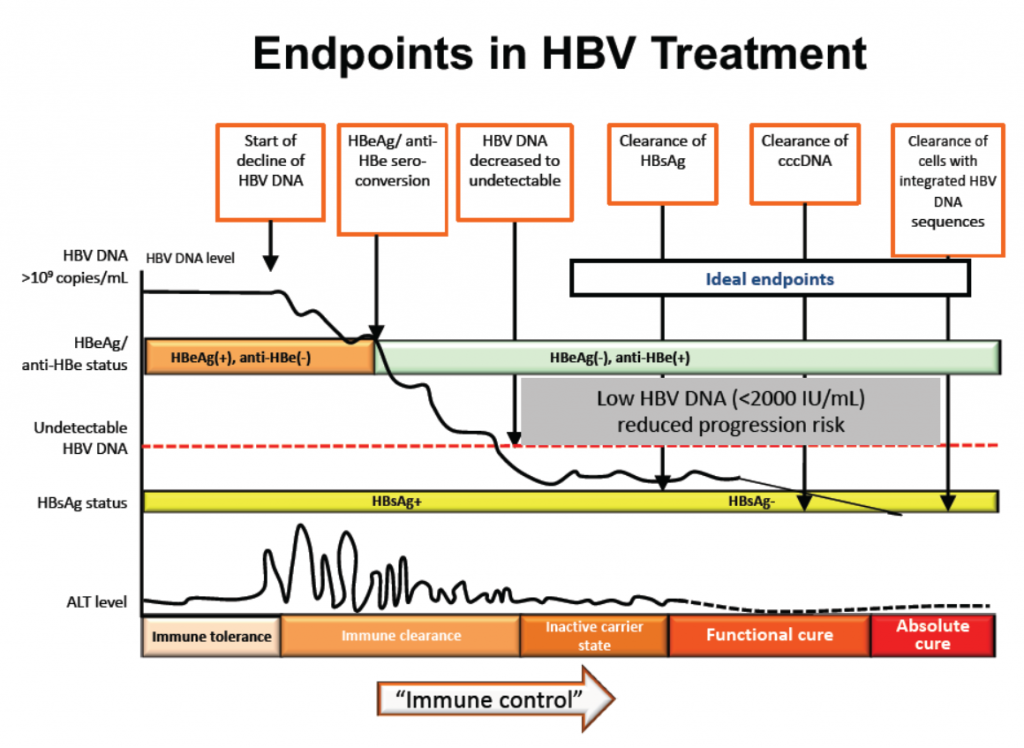

Since current hepatitis B treatment cannot completely cure the disease, the aim is to suppress the virus sufficiently to prevent liver cirrhosis, liver failure, or liver cancer, and thus improve survival.

How current hepatitis B treatment works

The hepatitis B virus produces bits of itself in its replication process in the body. One form of hepatitis B treatment drugs target various parts or stages of this replication process; others seek to enhance the body’s immune system to fight against the virus.

The various bits from the replication process and the body’s response to it are the markers which hepatitis B testing looks for, to find out if someone has hepatitis B, or has been infected with it in the past and recovered. Key among these markers is the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), the presence of which indicates chronic hepatitis B. The loss of surface antigen is accepted as one of the key indicators that treatment is working.

Generally speaking, the accepted indicators that treatment is working in achieving the goals of maintaining liver health and improving survival are:

- normal ALT levels,

- loss of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg),

- undetectable hepatitis B DNA and

- the appearance of hepatitis B e-antibodies (antiHBe).

The thinking is that when treatment achieves the above results, functional cure is achieved.

Do these indicators, or end points as they are referred to, really lead to better outcomes for people? According to Prof. Lim Seng Gee, Director of Hepatology, National University of Singapore, meta analysis shows significant benefits from the loss of HBsAg:

- 72% reduction in liver decompensation,

- 70% reduction in liver cancer, and

- 78% reduction in liver transplant or death.

These outcomes apply across all sub groups including co-infection, treatment history and race (ethnicity).

Why stop treatment at all?

The idea of looking for a functional cure is that when it is achieved, treatment can stop. But why stop treatment at all? There are a few reasons why treatment cessation is being considered even though the treatment is working to successfully suppress the virus.

Long term therapy presents challenges including:

- Risk of developing resistance to the drugs.

- Significant side effects such as bone loss and kidney damage.

- Cost of treatment – for the individual if drugs are not subsidised, or for the health system if they are. This factor is an important consideration in countries with limited health resources.

- Adherence – for all sorts of individual reasons, sticking to long-term treatment can often be a problem.

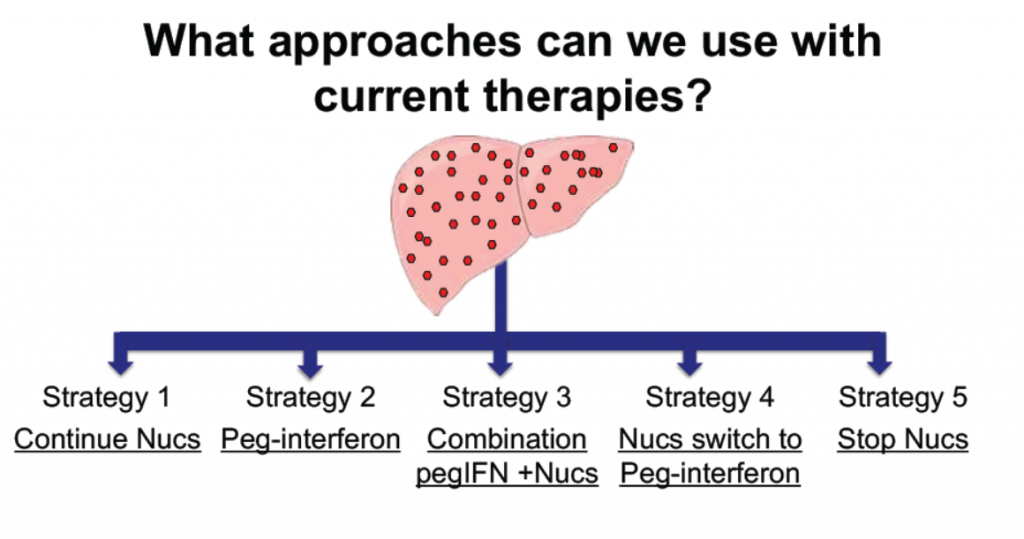

Accepting that functional cure is something to aim for, there are a range of strategies being looked at to get there. These include:

- using current drugs that target the replication process (nucleoside analogues),

- using pegylated interferon (pegIFN),

- using nucleosides and pegIFN in combination or in sequence, or

- stopping nucleoside analogues.

Strategies for achieving hepatitis functional cure using currently available therapies

Studies show that while a combination of pegIFN and nucleoside analogues (NA) produce the best outcomes with over 6.5% achieving HBsAg loss, and that pegylated interferon clearly outperformed NAs, the overall results of less than 10% indicates that new therapies are needed to achieve functional cure.

However, there are exciting possibilities in the strategy of stopping nucleoside analogue treatment. Studies have shown that when those treatments are stopped, there is a rebound of HBV DNA and ALT and this stimulates body’s immune response which then reduces the HBsAg level. The likelihood of HBsAg loss is related to the level of HBsAg at the end of treatment. The lower thelevel of HBsAg, the higher the chances of HBsAg loss (and with it a functional cure). At levels of less than 100 IU/mL at the stopping of nucleoside analogues, the surface antigen loss ranged from 21% to 58.5%.

For people on hepatitis B treatment, the big concern is whether the virus will reactivate once treatment ceases. Studies have shown that when the immune system is suppressed, as when undergoing immune-suppression therapy, the virus will reactivate in around 15 % of people even though they’ve had HBsAg loss, with a reactivation rate as high as 72% in some cases.

Despite relatively poor results, ongoing studies and research into new therapies and strategies mean that, until a real cure is found, the approach of treating hepatitis B with the aim of a functional cure is here to stay.

So if you have hepatitis B and have reached a stage where your specialist is advising you to start treatment, bear in mind that this is a changing field. While it may look like you’ll have to be on life-long treatment, it may not be the case as new therapies develop.

First published in Hepatitis SA Community News. More stories: https://hepatitissa.asn.au/magazine/477-issue-88-december-2020

Sources:

– Achieving functional cure in hepatitis B – Prof Lim Seng Gee, National University Hospital, Singapore, 2020

– Nucleos(t)ide analogues for chronic hepatitis B: Cessation of treatment – Prof Alex Thompson, St Vincent’s Hospital, Melbourne 2016

– Slides courtesy of Prof Lim S.G. via Singapore Hepatitis Conference (shc-sg.com)