Hepatitis C was one of the unintended consequences of haemophilia treatment before blood products could be tested for the virus. Since the introduction of new highly effective drugs for hepatitis C in 2016, most people with haemophilia in Australia have been cured of the infection.

Gavin Finkelstein is the president of Haemophilia Foundation Australia. He has lived with haemophilia for his whole life, and with hepatitis C since childhood. For World Hepatitis Day, Gavin was kind enough to tell us his story of living both conditions and how he was cured of hepatitis C.

Until at least 1995, people in Australia with haemophilia and related bleeding disorders were totally reliant on blood products for all of our treatment.

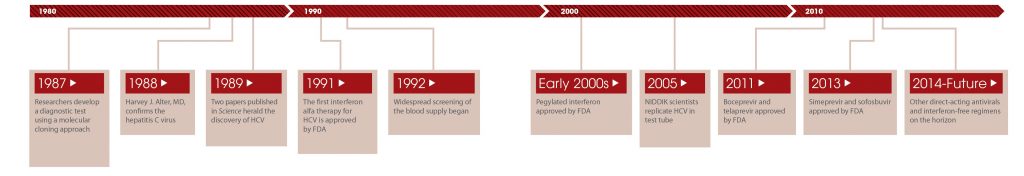

In my case I was born in 1962 and when I was young I was treated with bottles of whole blood that were infused (each over a 12-hour period) to resolve bleeds. This would happen anywhere between 10 and 50 times a year. This means I was probably infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) before I was 5 years old, and then reinfected perhaps hundreds of times over the years. Although HCV has existed in humans for perhaps thousands of years, it was not properly identified until 1989, so there was no way to identify it in the blood of a donor.

Over the years our treatment products were refined, but they were still blood products. For example, we went from whole blood to blood plasma-based products, which were in smaller volumes for treatment, and which didn’t require extended hospital stays. I would be injected with the blood plasma product (called cryoprecipitate) and then go home. I no longer had to be an “in-patient”, waiting for the bottles of blood to empty into me over a 12-hour period.

Another later innovation was plasma-derived clotting factor concentrate: each batch of concentrate was made up of about 10,000 donations pooled together, so the risk for HCV infection by a bloodborne virus was significantly high—if even one of those donors had hepatitis C, it would end up in the pooled mix.

Canaries

Haemophiliacs were often considered to be “the canaries in the mineshaft” if there was a blood-borne virus infecting recipients of blood products. This was shown in the early 1980s, when large numbers of the haemophilia community were infected with HIV because of our total reliance on blood products: before there was an HIV test, the poorly understood virus had made its way into the donated supply.

After this, our treatment products were heat-treated to destroy the HIV virus. I was fortunate to miss out on HIV, but I was told in 1990 that I had what was then called “non-A, non-B hepatitis”, which we now know as hepatitis C. “Don’t worry about it,” I was told. “There is nothing we can do about it anyway!” Heat treatment of blood products to inactivate HCV was introduced very early in the 1990s, but by then it was too late for a vast number of our community’s members.

In early 1994 I was properly diagnosed with hepatitis C and it had a profound effect on me. I didn’t know if I was going to live! Was there treatment? What was going to happen to me? There was so little information available. I became depressed, I ended the relationship I was in (I didn’t want my girlfriend to see me get sicker and die), I wasn’t working, and I became withdrawn, convinced that this was the end.

…it had a profound effect on me. I didn’t know if I was going to live!

It wasn’t until 2001 that I undertook combination therapy—first Interferon/ribavirin therapy, and then Peg-Interferon/ribavirin—which consisted of over 200 injections of interferon and over 2,000 ribavirin pills over what ended up being an 18-month period. This was when combination therapy, as difficult as it was, was the best hope of being cured of HCV.

I continued to work during this whole treatment period, often getting asked when arriving at work if I had taken my “grumpy” pills. I experienced all the side-effects, and it felt that my brain was just barely ticking over. It cost me promotions at work, I often made mistakes, and I had to be managed during the whole treatment process. All of my work colleagues and bosses knew and had received letters advising of the possible consequences of the treatment, but it still was a monumental effort to work the whole time. And in addition, I was volunteering with Haemophilia Foundation WA (HFWA) and Haemophilia Foundation Australia (HFA). Each evening and weekend I used to collapse, each weekday morning I would drag myself begrudgingly out of bed to attend work.

I completed treatment in 2003, clearing HCV—and then I relapsed 6 weeks later, which was utterly devastating. I decided against trying treatment again for a few years, and ended up waiting and hoping that newer, better treatments might become available.

In 2004 I was part of the HFA team that presented at the Commonwealth Inquiry into Hepatitis C and Blood Supply in Australia, a landmark inquiry whose recommendations still haven’t been addressed or carried out, which has unfortunately resulted in a variety of serious impacts to members of the bleeding disorders community over the 17 years since.

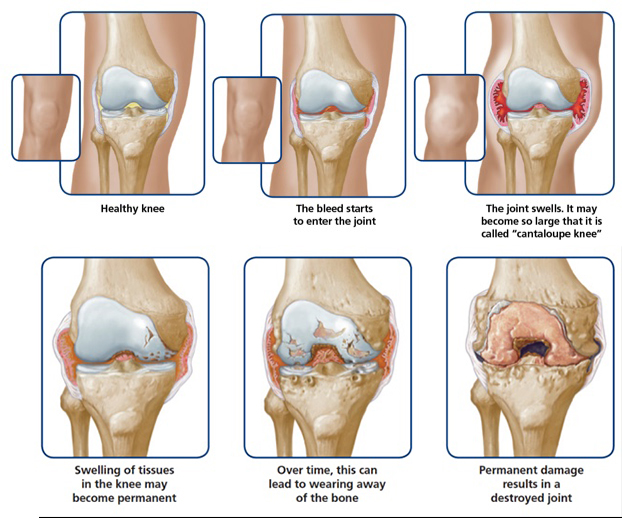

In 2005 I decided it was time to retire due to the impact of the HCV (I was suffering from constant tiredness, a lack of motivation, a foggy head, and feeling generally burnt out) and the physical impacts of haemophilia (I was due for my second knee replacement and I was experiencing chronic arthritis in my ankles, elbows and knees). But in the same year I became president of HFA, which is a voluntary position, and which has been an amazing and rewarding experience. I’ve developed new skills, seen advances in treatments for bleeding disorders and HCV, met amazing people worldwide, and I hope, been able to represent my community in a way that has been of benefit to all.

In 2007 I decided to take the plunge again and try treatment once more with Peg-Interferon/ribavirin. After 12 weeks, sadly, I wasn’t PCR-negative, which meant the treatment wasn’t working, so I discontinued it.

I continued to monitor and follow treatment changes and advancements, bypassing triple therapy (which used Peg-Interferon/ribavirin and a direct-acting antiviral agent) because of the horrendous side-effects experienced by everyone I spoke to about, and because it only had a 40-60% of a successful outcome.

In 2016, when the new generation of direct-acting antiviral medications targeting HCV were approved for use on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), I started treatment as soon as it could be organised. After completing the 16 weeks of treatment, which was now just a single tablet a day with no side-effects, I was cured of the hepatitis C which I had been living with for a least 35 years. The fog finally lifted, and I felt great!

Of course, while it was fantastic to be cured of HCV, I still had to deal with the ongoing lifelong consequences of haemophilia: deteriorating joints, chronic arthritis and accelerated ageing. People living with both with bleeding disorders and HCV deal with an overload with chronic health conditions, and it can be hard to prioritise your care and manage your health, especially when hepatitis symptoms like fatigue and brain fog compound your health problems and sap your energy. Having access to a simple HCV treatment with minimal side-effects was genuinely great for us.

… there is no cure for haemophilia, this is a lifelong task. But it is a much easier one without the added burden of hepatitis C.

Nearly all members of the bleeding disorders community in Australia have now been cured of hepatitis C, which is an amazing achievement, but some still live with ongoing issues connected with liver cancer or cirrhosis. Often they need to retire early, which brings with it financial stress and the possibility of spending decades of your life in and out of hospital wards. Having cleared one hurdle, I can focus more on managing my haemophilia. As there is no cure for haemophilia, this is a lifelong task. But it is a much easier one without the added burden of hepatitis C.

If there is anyone out there still living with haemophilia and HCV who hasn’t been in contact with the HF or the Haemophilia Treatment Centre clinicians, please know that there are no impediments to treatment now; there are just the fantastic results that we have all experienced. It is certainly very much worthwhile.

For more information on haemophilia, visit Haemophilia Foundation Australia.

From the archive: see Hepatitis SA’s special magazine issue on haemophilia and hepatitis C here.

Thank you for sharing Gavin, I work in the blood borne virus sector in SA but we currently don’t see anybody living with Haemophilia alongside BBV (HIV / HBV or HCV) Your story reminds me about so many people out there who inadvertantly ended up with a blood borne virus prior to blood being screened and how living with a BBV has potentially complicated the clinical outcome for those vulnerable individuals.

I’m really glad you were able to clear the Hep C virus in 2016, the new treatments were/are truly amazing!